Florida-based researchers said yesterday they have uncovered early lab evidence that seems to affirm a suspicion some experts have had about Zika—that earlier dengue illness might boost the severity of Zika virus infection.

Scientists have known about Zika virus since its discovery in the 1940s, but it didn't appear on anyone's radar as a serious disease threat until it became associated with serious complications such as Guillain-Barre syndrome and birth defects such as microcephaly, in which babies are born with small heads and malformed brains.

Both viruses are members of the flavivirus family, and both are carried by Aedes mosquitoes. Researchers have already seen a similar pattern, called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), in patients sequentially infected with different dengue virus strains. And ADE has been seen with Zika virus as the result of antibodies from other flaviviruses.

Lab test-drive strengthens hypothesis

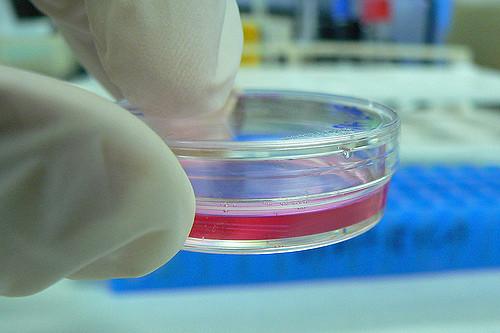

Case control studies are under way in the outbreak region to, among other tasks, tease out the role of prior dengue infections or coinfections. The new cell-culture study, however, provides an early clue about the plausibility. The group from Florida Gulf Coast University published its findings yesterday in bioRxiv, a prepublication Web portal for scientific studies.

In their experiments, the investigators set out to see if neutralizing human anti-dengue monoclonal antibodies (HMAbs) or human dengue immune sera had any impact on Zika virus in cell culture.

Their tests revealed that dengue HMAbs cross-react, don't neutralize, and enhance Zika infection in the lab setting. Also, the team found that dengue immune sera had varied degrees of neutralization against Zika virus and also enhanced infection.

Implications for outbreak response

Results suggest that preexisting dengue immunity will boost Zika virus infection in clinical settings and may ramp up disease severity, researchers concluded, noting that a clear understanding of the relationship between the two diseases is crucial for influencing the public health response.

For example, they said Zika virus might spread more easily and persist more strongly than expected in areas where dengue is endemic. It's not clear yet what the pattern will be in areas where Aedes mosquitoes are present, they noted. "One hopeful possibility is that ZIKV [Zika virus] spread may be slower in areas where DENV [dengue virus] immunity is low," the group wrote.

The findings also have implications for both dengue and Zika vaccines, they said. Given the serum findings, perhaps a single vaccine could protect against both dengue and Zika virus.

Other developments

- The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) today announced $5 million in funding for 20 health centers in Puerto Rico to assist with the battle against Zika virus. It said the funds will help expand family planning and contraceptive services, outreach and education, and staffing. Puerto Rico has reported 474 Zika cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with the number expected to rise.

- A group of Democrats in the US House of Representatives yesterday introduced an emergency supplemental bill to address the Zika virus threat, according to a statement from Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi of California. The statement criticized Republican members of the House Appropriations Committee for blocking emergency resources twice. Late last week Senate members signaled that discussions were under way to take up Zika funding.

See also:

Apr 25 bioRxiv study