A new study suggests race, ethnicity, and income inequality in high-income countries (HICs) are associated with a higher risk of drug-resistant infections, researchers reported yesterday in JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance.

In a systematic scoping review, researchers from the UK Health Agency and Imperial College London reviewed literature on health inequalities and the risk of antibiotic-resistant infections in HICs that was published from 2010 through February 2024. Although antibiotic use is the primary driver of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), previous studies have highlighted the intersection between poverty, social deprivation, health inequalities, and AMR, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The aim of the study was to explore how these factors may influence AMR risk in HICs.

"This focus is particularly important as HICs face different structural and healthcare challenges to LMICs, with growing evidence of widening inequalities, particularly in the UK and USA," the study authors wrote.

Broader social and contextual factors

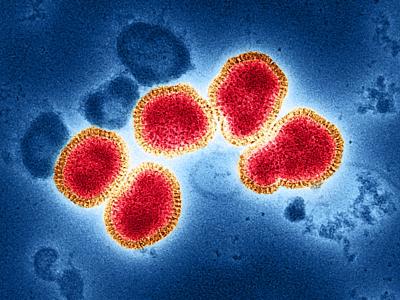

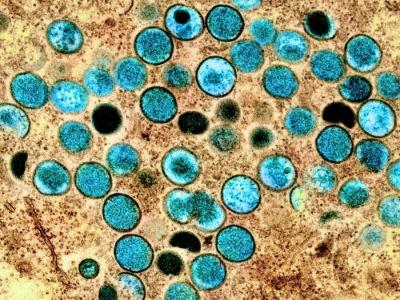

Of the 331 papers reviewed, 18 were included in the final analysis. Twelve of the studies were conducted in the United States, and the rest were from the United Kingdom (2), New Zealand (2), Australia (1), and Europe (1). The most frequently identified pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus (13 studies) and Escherichia coli (5). Ethnicity/race was the most frequently cited element of health inequality (11), followed by deprivation (7) and age (7).

In the United States, Black patients had methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) rates that were two to three times higher than White patients, despite declines in overall MRSA rates. In Australia and New Zealand, indigenous and Maori/Pacific Peoples had a higher burden of MRSA than other ethnic groups.

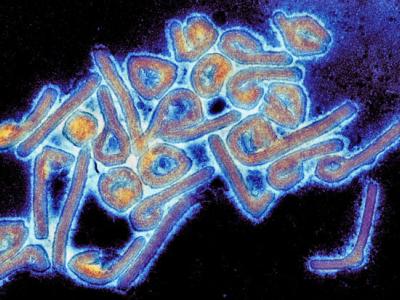

Similar racial disparities were also observed for streptococcal infections, with higher rates of penicillin-resistant S pneumoniae observed in Hispanic patients than in non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Drug-resistant E coli infections were more prevalent in Maori populations in New Zealand and in low-income or high-deprivation groups in the United States and Europe, while income inequality correlated with resistance in Enterococcus, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas across Europe.

"These findings underscore the importance of considering the broader social and contextual factors in understanding and addressing bacterial infections and AMR," the authors concluded.