New surveillance data presented today by the World Health Organization (WHO) show that bacterial infections around the world are becoming increasingly difficult to treat. And some regions are being hit harder than others.

The latest report from the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS), which includes data submitted by more than 100 countries, reveals that 1 in 6 laboratory-confirmed common bacterial infections were resistant to antibiotics in 2023. From 2018 through 2023, antibiotic resistance rose in more than 40% of the bug-drug combinations monitored, with an average annual increase of 5% to 15%.

But resistance varies widely among regions. In the WHO's Southeast Asian and Eastern Mediterranean regions, an estimated 1 in 3 common bacterial infections are drug-resistant, compared with only 1 in 10 in Europe. In Africa, 1 in 5 are resistant to treatment. The problem is generally worse in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that have weak healthcare systems and limited surveillance capacity.

"These findings are deeply concerning," Yvan Hutin, MD, PhD, director of the WHO's antimicrobial resistance (AMR) department, said at a press briefing. "Antibiotic resistance is not only widespread and increasing, but it's also unevenly distributed across the globe."

Effectiveness of first-line treatments 'increasingly compromised'

The WHO says the 2025 GLASS report is its most comprehensive assessment of AMR since it established the surveillance system in 2015. The 104 countries that submitted the data represent 70% of the world's population.

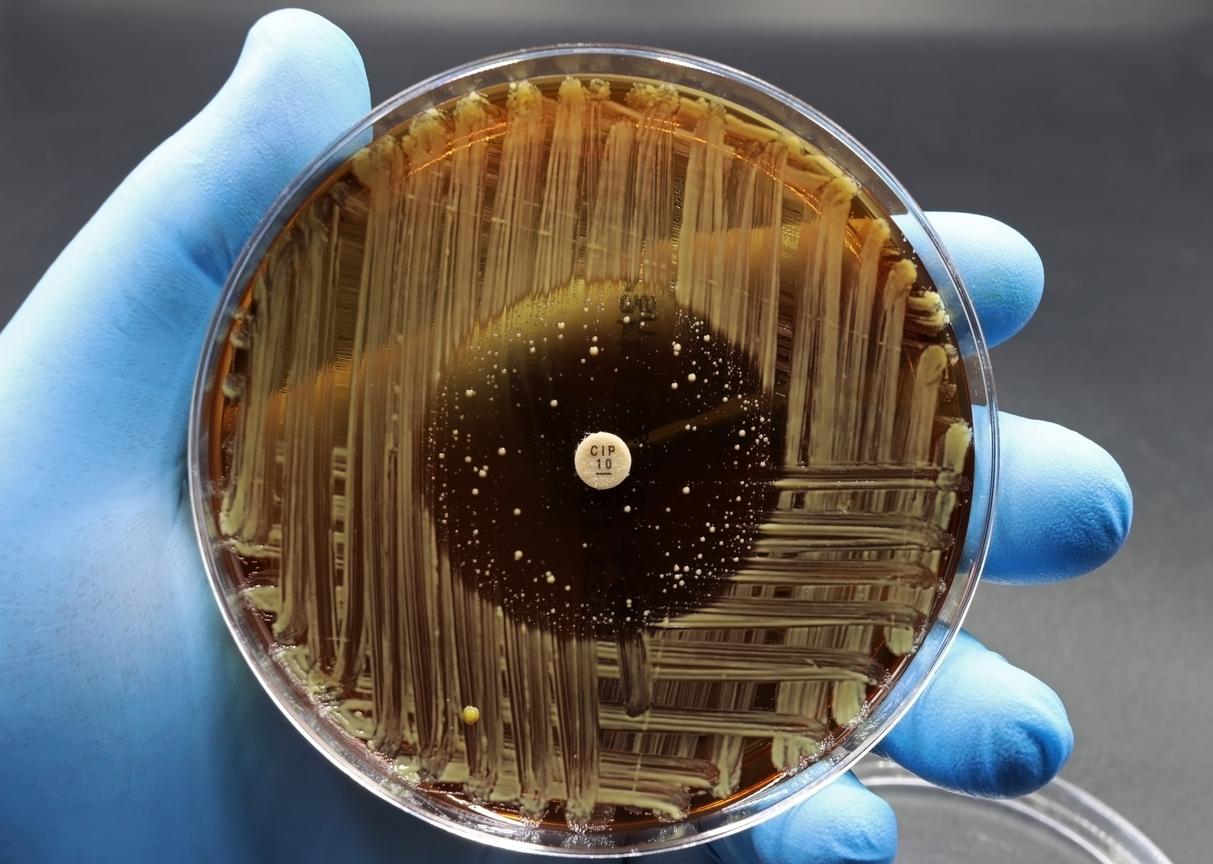

The analysis covers more than 23 million bacterial infections and provides resistance prevalence estimates across 22 antibiotics used to treat urinary, bloodstream, gastrointestinal, and urogenital gonorrhea infections caused by eight bacterial pathogens (Acinetobacter spp, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, non-typhoidal Salmonella spp, Shigella spp, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae).

Median antibiotic resistance was most common in urinary tract (1 in 3) and bloodstream infections (1 in 6) and less so in gastrointestinal (1 in 15) and urogenital gonorrheal infections (1 in 125). In urinary tract infections caused by E coli and K pneumoniae, which are among the most common bacterial infections experienced by women worldwide, resistance to first-line antibiotics was typically higher than 30% in most countries.

"The effectiveness of first-choice treatments for common infections of the bloodstream, urinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract is increasingly compromised," the report states.

As previous GLASS reports have documented, the most concerning increase in resistance is in gram-negative bacteria commonly found in bloodstream infections, which are among the most serious type of bacterial infection. For example, resistance to the first-line antibiotic treatment (third-generation cephalosporins) was found in 44.8% of E coli and 55.2% of K pneumoniae bloodstream infections. In Africa, resistance to third-generation cephalosporins exceeded 70% for both pathogens.

Antibiotic resistance is not only widespread and increasing, but it's also unevenly distributed across the globe.

The report also highlights increasing resistance in gram-negative pathogens to "Watch" antibiotics, which are the broad-spectrum antibiotics the WHO has determined should be used for more severe infections. Notably, 54.3% of Acinetobacter bloodstream infections were resistant to carbapenems, which have seen increasing use as resistance to first-line treatments has risen. In Southeast Asia, the frequency of carbapenem resistance in K pneumoniae bloodstream infections reached 41.2%.

"This is a concern, as these antibiotics are essential for the treatment of severe infections," the report notes. Once a pathogen becomes highly resistant to carbapenems, treatments options become severely limited.

But while AMR is a problem that can affect people in all countries, the report further confirms that the burden is heaviest in LMICs. These countries tend to have weaker health systems, limited diagnostic capacity to correctly detect bacterial infections and identify the best antibiotic, and restricted access to the essential antibiotics needed to properly treat infections, resulting in undertreatment and poorer outcomes.

"Simply put, the less people have access to quality care, the more they're likely to suffer from drug-resistant infections," Hutin said.

But Hutin and his colleagues caution that interpreting the data from LMICs is tricky, because these countries also tend to have weaker surveillance systems that test fewer patients and may submit data only from tertiary hospitals, which treat the most severe infections. While these countries may have genuinely higher resistance rates, the sampling bias could lead to overestimates of resistance prevalence.

"Countries need to do a much better job of collating representative data so that we can have a comprehensive and reliable picture of the situation at the country level," said Silvia Bertagnolio, MD, head of the WHO's AMR surveillance, evidence, and laboratory strengthening unit.

Data more comprehensive, but gaps remain

Despite the concerning rise in resistance, WHO officials say they are encouraged that more countries are submitting data to GLASS and enabling the creation of global AMR estimates, which to date has not been possible. They note a fourfold increase in participation since the first report in 2016, when only 25 countries reported AMR data.

"The upward trend in participation in GLASS reflects increased awareness in countries of the value of global data-sharing as a common public health good," Bertagnolio said.

In addition, more countries are reporting antimicrobial susceptibility test (AST) results, which means they're either conducting AST more frequently in clinical care or broadening it to additional healthcare facilities.

But significant gaps remain. Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Western Pacific provide limited or no data to GLASS. In addition, fewer than half of the 104 countries that submitted data for 2023 reported that they had WHO-recommended core components of a robust national surveillance system. That all adds up to a picture that remains incomplete, Bertagnolio said.

The upward trend in participation in GLASS reflects increased awareness in countries of the value of global data-sharing as a common public health good.

Going forward, the WHO said improving the coverage and representativeness of AMR surveillance systems should be one of the top priorities for countries. The organization also called on countries to implement coordinated interventions that include antimicrobial stewardship, infection prevention and control, and improved access to water, sanitation, and hygiene. These interventions should be context-specific and tailored to local resistance patterns and health system capacity.

Finally, more investment in research and development of new antibiotics should be an urgent priority, the WHO said.