Aug 13, 2004 (CIDRAP News) – New findings suggest that far more people may be susceptible to variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) than was previously supposed, according to a report in the Aug 7 Lancet.

British researchers report finding evidence of vCJD in a patient who had a different combination of the genes for normal prion protein from that seen in other cases of the disease. The patient's genetic profile is more common in the general population than the type seen in previous vCJD cases, which suggests that the disease could be much more common than was previously believed, according to the article.

"This finding has major implications for future estimations of numbers of vCJD cases in the UK, since individuals with this genotype constitute the largest genetic subgroup in the population," says the article by Alexander H. Peden and colleagues from the National Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance Unit at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

The patient described in the report is the second person in the United Kingdom believed to have acquired vCJD from a blood transfusion. He or she died 5 years after receiving blood from a donor who later developed vCJD. British officials announced the case Jul 22 but gave few details about it at the time.

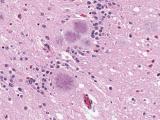

The blood recipient had no outward signs of the disease and died of unrelated causes, but the abnormal prion protein associated with vCJD was found in the spleen and in a cervical lymph node. The misshapen protein was not found in the brain, spinal cord, tonsils, or other sites where it is usually seen in vCJD patients.

The authors write that the patient could have acquired vCJD by eating meat products from a cow infected with bovine spongiform encephalopathy, but it is far more likely that the blood transfusion was the transmission route. The presence of abnormal prions in the spleen and cervical lymph node, but not in the tonsils or gut-associated lymph nodes, fits with intravenous rather than dietary exposure, the report says.

Genetically, the patient was described as a heterozygote at codon 129 of the prion protein gene, meaning his or her parents supplied different versions of the prion protein gene. In previous vCJD cases, patients were homozygous at that point, possessing identical genes from each parent.

James W. Ironside, senior author of the Lancet study, told the Associated Press that about 50% of whites share the genetic profile of the patient described, and about 35% have the genotype seen in the previous vCJD cases.

In the Lancet article, the researchers say those with the heterozygous genotype may have a longer incubation period for vCJD than those with the homozygous type. "A very lengthy incubation period might explain why no clinical cases of vCJD have yet been observed in this subgroup," they write.

The findings also raise the possibility that asymptomatic carriers of vCJD could spread the infection to others, "either by blood donation or by contamination of surgical instruments coming into contact with lymphoid tissues," the article says.

According to the UK Department of Health, 142 people in Britain have died of definite or probable vCJD since the disease was identified in 1996. Five people with probable vCJD are still living. Few new cases have been identified in recent months, leading to speculation that the disease has peaked in Britain.

But the new findings suggest that more cases could be on the way, according to the authors. In an Agence France-Presse report published Aug 6, Ironside said, "It's absolutely possible that there could be a new epidemic, because the cases we've seen so far may only be those who are unusually susceptible or have the shortest incubation periods."

In another article in the Aug 7 Lancet, a team of American and Canadian researchers reported that leucoreduction—the removal of white cells from blood—can reduce but not eliminate the risk of transmitting diseases like vCJD in blood transfusions. Leucoreduction is one of several measures used in the UK to prevent the transmission of vCJD.

The researchers collected blood from hamsters infected with scrapie and used a commercial filter to remove white blood cells. They found that the filtering removed 42% of the infectivity in the blood.

Peden AH, Head MW, Ritchie DL, et al. Preclinical vCJD after blood transfusion in a PRNP codon 129 heterozygous patient. Lancet 2004;364(9433):527-9 [Abstract]

Gregori L, McCombie N, Palmer D, et al. Effectiveness of leucoreduction for removal of infectivity of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy from blood. Lancet 2004;364(9433):529-31 [Abstract]

See also:

Jul 22, 2004, CIDRAP News article, "Another UK patient might have caught vCJD from blood"