Science, when done well, can be messy, imperfect, and slower than we wish. And it's ever-evolving. Unfortunately, in the time of a pandemic, we wish this weren't the case, as we all want and need immediate answers.

Public health policy—including COVID-19 response—should always be informed by the best data available and should evolve with scientific knowledge. But it should not be based on popular opinion or even well-meaning movements within the scientific community. Good science should precede policy, not vice versa.

From the very first cases in China, CIDRAP has been compiling and disseminating science-based information and straight talk on COVID-19. In fact, our dedicated team has been providing science-based, non-partisan coverage of infectious diseases for nearly 20 years. Our only agenda is to inform the public about what the scientific community knows and does not yet know about COVID-19. We take this same approach with cloth face coverings.

At the outset, I want to make several points crystal clear:

- I support the wearing of cloth face coverings (masks) by the general public.

- Stop citing CIDRAP and me as grounds to not wear masks, whether mandated or not.

- Don't, however, use the wearing of cloth face coverings as an excuse to decrease other crucial, likely more effective, protective steps, like physical distancing

- Also, don't use poorly conducted studies to support a contention that wearing cloth face coverings will drive the pandemic into the ground. But even if they reduce infection risk somewhat, wearing them can be important.

I've received increasing criticism in recent weeks because I've offered more nuanced messaging on whether everyone should wear cloth face coverings in public to protect against COVID-19 transmission—messaging that some view as unacceptable. The criticism has included a recent commentary by Masks4All proponents Jeremy Howard and Vincent Rajkumar, MD, that mischaracterizes my position on cloth face coverings and misrepresents the science of personal protection for COVID-19.

Again, I want to make it very clear that I support the use of cloth face coverings by the general public. I wear one myself on the limited occasions I'm out in public. In areas where face coverings are mandated, I expect the public to follow the mandate and wear them.

At the same time, I have been concerned about "message creep" since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) first recommended in April to use cloth face coverings without providing additional context regarding their use. Public health messaging should include a more precise discussion of the effectiveness of cloth face coverings in preventing transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. We need to be clear that cloth face coverings are one tool we have to fight the pandemic, but they alone will not end it. And we need to underscore the key role that physical distancing plays—even when you wear a face covering.

Guidance from agencies such as the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) make it clear that the use of face coverings in the community should be considered only as a complementary measure to other preventive tools such as physical distancing. They recommend that face coverings should be used as part of a comprehensive strategy, but that the use of a face covering alone is not sufficient to provide an adequate level of protection against COVID-19. A report by the Usher Network for COVID-19 Evidence Reviews (UNCOVER), similarly states that "The lower protective capabilities of a homemade mask should be emphasized to the public so that unnecessary risks are not taken."

I expressed these concerns in my Jun 2 podcast episode on masks, saying:

"[The general public] should be made aware that [cloth] masks may provide some benefit in reducing the risk of virus transmission, but at best it can only be anticipated to be limited. Distancing remains the most important risk reduction action they can take. ... The messaging that dominates our COVID-19 discussions right now makes it seem that—if we are wearing cloth masks—you're not going to infect me and I'm not going to infect you. I worry that many people highly vulnerable to life-threatening COVID-19 will hear this message and make decisions that they otherwise wouldn't have made about distancing because of an unproven sense of cloth mask security."

These concerns remain true today, particularly after CDC leadership made the unfortunate statement that the US epidemic could be driven to the ground if everyone wore face coverings for the next 4 to 6 weeks. If this were true, why do we need a vaccine to end this pandemic? Just "mask our way" to control. When put into this context, it's obvious how the CDC statement is unrealistic and misleading. Why do places like Hong Kong, which has a requirement for the use of cloth face coverings in public at a risk of a $HK 5,000 fine, have their highest number of community-acquired COVID-19 cases since the beginning of the pandemic?

In the same Jun 2 podcast, I further dispelled notions that I'm "anti-mask":

"I'm working with a group of some of the country's most renowned technology leaders to develop a reusable N95 mask that could be washed hundreds of times without losing its electrostatic charge and fit…If these masks can become a reality and many, many millions of them made and distributed to the public around the world in the next few months, this could be a real game-changer. So anyone who claims I don't think masks are important, they are just plain wrong. I do. In fact, I think about it frequently as my daughter, who is a neonatologist, goes to work every day to a potential COVID situation. I think about that all the time."

We mustn't overreach what the current data tell us. Authors and journal editors have a responsibility to clearly communicate the limitations of study designs and thus not overstate the results. As consumers of these data, public health officials and academics have the responsibility to assess and critique studies with unfailing rigor.

Let me give just one recent example. A letter last week from three deans of schools of public health that called for universal masking cited just one study on mask effectiveness, yet that study had egregious and much publicized methodologic flaws—so much so that it prompted a call to the journal editor for its retraction from more than 50 subject-area experts. The deans obviously were unaware of this call for retraction and must not have reviewed the study sufficiently to appreciate its critical deficiencies. If we fail to assess studies on cloth face coverings critically, we fall prey to confirmation bias and risk developing policy not based on sound scientific evidence.

In the same vein, we must not conflate the sheer number of recent studies on cloth face coverings with quality. A series of papers have been published in recent weeks addressing the effectiveness of cloth face coverings, but they collectively lack scientific rigor for a variety of reasons, including a much-touted meta-analysis that did not even include studies of cloth face coverings in the community but rather included studies largely on surgical masks and N95 respirators used in healthcare settings.

It is critical that not just more research, but high-quality research be conducted so that the scientific community can assess the effectiveness of cloth face coverings in reducing COVID-19 transmission. Transparency is sorely needed in two areas in particular to help us parse out the impact of cloth face coverings: the setting in which the studies are conducted (e.g., hospital settings vs community-based settings) and whether they assess respirators, surgical masks, or cloth face coverings.

As much as I applaud the spirit of Masks4All, Mr. Howard and Dr. Rajkumar's commentary does not accurately reflect my and CIDRAP's perspective on cloth face coverings nor the science of personal protection. Many uncertainties about SARS-CoV-2 remain.

As scientists, Mr. Howard, Dr. Rajkumar, and I will agree, I'm sure, that being truthful about these uncertainties is vital. The public can make good decisions only when officials lay out both the knowns and unknowns. Thus, I think it's important to address, in some detail, some misstatements and misunderstandings reflected in their article.

Response to Howard and Rajkumar commentary

JH & VR: "WCCO radio announced that "Coronavirus expert Dr. Osterholm questions guidelines on cloth masks, says they don't stand up to virus' air assault", quoting Osterholm as saying "Cloth masks, I think… have little impact, if any."

MTO: Mr. Howard and Dr. Rajkumar fail to provide additional context from this May 4 interview, in which I said the following:

"We know that the virus can be transmitted by what we call [aerosols—mistakenly termed 'air assaults' by WCCO]—it's the tiniest of particles. If anything comes in along the side of the mask or escapes that way, then it really minimizes both [the] protection for the individual who used the mask or the protection for others so that if I'm infected, I don't transmit to them. That's when you get into the surgical masks and to the cloth masks. And quite honestly, the data for both is lacking that they are major impediments [in either] getting infected or infecting others."

"People want to wear a mask. That's great. But I think we're going to show in the end that many more health care workers were infected by working with only surgical masks and not N95 [masks]. I realize and understand the shortage of N95 … I get that [surgical masks] are better than nothing, but I don't think that it offers anywhere near the protection that we need for this virus."

While the science on this issue remains ongoing, numerous limitations have plagued studies completed to this point, complicating any meaningful judgment as to the role that cloth face coverings can play in helping control this pandemic. Quality data assessing the effectiveness of cloth face coverings are still lacking, as noted by Roger Chou, MD, and colleagues in a recent rapid review article and follow-up letter in the Annals of Internal Medicine. My statements align with advice offered in the aforementioned UNCOVER report—which recommends emphasizing the lower protective capabilities of cloth face coverings to the public.

JH & VR: "In another WCCO appearance he stated that 'the Minneapolis mask mandate could do more harm than good'."

MTO: Again, important context is missing from this selected quote I provided in a May 22 interview. I said the following:

"If people want to wear them, they should wear them. I worry that any benefit that could come from those will become undone by people believing they have more protection than they do. In the end, we do more harm than good."

My position and concern about the potential drawbacks of the use of cloth face coverings is supported. As was mentioned earlier, similar sentiment is expressed by the ECDC and WHO.

JH & VR: "The Cape Charles Mirror stated "You realize, the stupid masks you wear to the store don't do anything, right", quoting Osterholm: "If you want to wear a cloth mask, use it. Know that I don't believe, or none of my colleagues, that this is going to have a major positive impact."

MTO: My quote, which is featured in the latter half of the statement above, was provided during an Apr 3 interview with WCCO. The first quote featured in their statement above is not mine. Rather, it is the headline of the May 3 article in the Cape Charles Mirror, which was likely selected by their editor. I have never been interviewed by the Cape Charles Mirror, and I had absolutely no role in shaping the headline of their article.

It is disappointing that Mr. Howard and Dr. Rajkumar chose to include the sensationalized headline of that article rather than linking readers to the original WCCO source. My disappointment is even further expressed in a similar commentary written by their colleague, MarkAlain Déry, DO, where this same inflammatory quote is directly and wrongfully attributed to me. Mr. Howard and Dr. Rajkumar are both listed as contributors to that commentary.

JH & VR: "In April CIDRAP published a piece from Lisa Brosseau, an industrial hygienist, and Margaret Sietsema, a public health academic, which is full of uncited claims, falsehoods, and misunderstandings. Unfortunately, the article was not submitted for peer review, nor was any mechanism for public comment made available, despite Osterholm's stating a concern about studies that are 'being widely distributed before they are reviewed and published'. It claimed, without any references, that 'sweeping mask recommendations… will not reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission, as evidenced by the widespread practice of wearing such masks in Hubei province'. No references or data were provided to back up this claim."

MTO: The piece is clearly labeled in capital letters as a commentary. The common expectation of commentaries is that they are not peer-reviewed.

The statement about "sweeping mask recommendations" is well-supported by citations further down in the article. As of this writing, few data support that cloth face coverings will help flatten the curve. In countries and cities where mask wearing is more likely to be followed by most of the population, there are now significant and ongoing outbreaks. The authors of the commentary last week added a statement to their comment clarifying that they support people wearing face coverings where they are mandated but encouraging people to continue to limit their time spent indoors near potentially infectious people and to not count on a cloth face covering to protect them or the people around them. Avoiding or spending as little time as possible in crowded, indoor, poorly ventilated places should be a higher priority.

The Apr 1 Brosseau and Sietsema commentary described two important and key features that govern the performance of anything placed on the face to either prevent emission of particles or protect the wearer from inhaling hazardous particles: filtration efficiency and fit. Each of these was described in much detail, with many citations, explaining the basic principles that govern each and the tests required to evaluate each.

The authors found very few studies of the fit of cloth face coverings. But, drawing from their extensive expertise with respirators and surgical masks and the limited data on cloth face coverings, they concluded that, because cloth face coverings demonstrate very low filter efficiency for the smaller particles generated during breathing and talking, even a well-fitting face covering would not be very effective at lowering the emission or inhalation of small infectious particles.

The data today are even more strongly supportive of close-range small-particle inhalation than they were when the commentary was published, as evidenced by (1) a recent letter to the WHO from 239 scientists describing the importance of small particle inhalation as an important mode of transmission and (2) a high amount of presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission—that is, without large droplets from coughing and sneezing.

JH & VR: "Looking at the actual data, however, shows that it supports the opposite conclusion – masks may have been critical in controlling the Hubei outbreak. A report from Guo Yi in HK01 pointed out that up until Jan 22 most people in Wuhan were not wearing a mask. The next day, the government started requiring masks in public. Wuhan had their peak number of cases two weeks later, on Feb 4, and since then case numbers have been decreasing. Two weeks is exactly the amount of time we'd expect to see a public health intervention like this take to impact documented cases."

MTO: A key point is that on Jan 23, when officials mandated masks in Wuhan, they also implemented an extremely strict lockdown. The conclusion that masks played a critical role in controlling the Wuhan outbreak is unrealistic. This "evidence" speaks directly to my concern that public policy on this issue is not being guided by quality science.

JH & VR: "The article cites 4 references for a claim that "Household studies find very limited effectiveness of surgical masks at reducing respiratory illness in other household members". However, none of the references make this claim or show data to support it. Their reference 22, for instance, is a meta-analysis which lists the results of each analysis they looked at, and concludes 'If the randomized control trial and cohort study were pooled with the case–control studies, heterogeneity decreased and a significant protective effect was found'."

MTO: The commentary authors agree that not all of the meta-analyses they cited were appropriate to this statement. Thank you for pointing this out. Last week they revised the text to more accurately reflect the evidence.

JH & VR: "Brosseau and Sistema [sic] claim that there was a 'failure of cloth masks required for the public in stopping the 1918 influenza pandemic', citing a 1920 paper by WH Kellogg, a claim repeated in a polemic from Osterholm in a recent podcast. This is a misunderstanding of the evidence. In fact, Kellogg relied on looking at the difference in results between San Francisco, where masks were required, and other regions where they were not. Using a single data point in this way is an example of the ecological fallacy, and is not considered in modern epidemiology as meaningful evidence. However, even if we do accept that the San Francisco mandate was ineffective, we should also note what Kellogg said about why: his belief was that the problem was that masks were only used outside, where transmission was less likely. In Australia, mask-wearing by healthcare workers was thought to be protective during the 1918 pandemic, and given evidence of transmission in a closed railway carriage, it was concluded that mask wearing 'in closed tramcars, railway carriages, lifts, shops, and other in enclosed places frequented by the public had much to recommend it.' Today, nearly all places that require masks for COVID-19 only require them inside."

MTO: An editor's note at the top of the Kellogg paper reads:

"Masks have not been proved efficient enough to warrant compulsory application for the checking of epidemics, according to Dr. Kellogg, who has conducted a painstaking investigation with gauzes. This investigation is scientific in character, omitting no one of the necessary factors. It ought to settle the much argued questions of masks for the public."

In their introduction, Kellogg and MacMillan discuss several 1918 articles on the protective value of cloth masks. They demonstrate a clear understanding of several important issues that limited the quality and usefulness of these studies, such as lack of a control when comparing two different time periods, one with and one without masks; missing data about mask design and comparison data in an anecdotal report about no scarlet fever cases in a hospital ward; failure to recognize the important of "possible leakage around the edge of the mask, which occurs in actual practice" for a laboratory study of droplets emitted by mask-wearing subjects. Clearly, Kellogg was a thoughtful and insightful researcher.

Kellogg and MacMillan note: "If we grant that influenza is a droplet-borne infection, it would appear that the wearing of masks was a procedure based on sound reasoning and that results should be expected from their application." They note that studies by the California State Board of Health "did not show any influence of the mask on the spread of influenza in those cities where it was compulsorily applied," which led to mask recommendations rather than mandates, leaving it to local jurisdictions to determine if masks should be "universally worn."

The authors describe the discussions held with epidemiologists about the failure of masks: "It had long been the belief of many of us that droplet-borne infections could be easily controlled in this manner." They did not encounter any public pushback: "Masks, contrary to expectation, were worn cheerfully and universally, and also, contrary to expectation of what should follow…no effect on the epidemic curve was seen. Something was plainly wrong with our hypotheses."

The authors explored several possible reasons for failure, including (1) "the large number of improperly made masks that were used," (2) "faulty wearing of masks, which including the use of masks that were too small, the covering of only the nose or only the mouth", and (3) wearing masks at inappropriate times. For the latter circumstance, the problem was that "masks were universally worn in public, on the streets, in automobiles, etc. where they were not needed, but where arrest would follow…and…were very generally laid aside when the wearer was no longer subject to observation by the police, such as in private offices and small gatherings of all kinds. This type of gathering with the attendance social intercourse between friends, and office associates seems to afford particular facility for the transfer of the virus."

Kellogg and MacMillan noted that they undertook a series of experiments on the performance of gauze masks because more information was needed about their application and limitations so that masks would not be "permanently discredited." "If, as we believed, the gauze mask is useful as a protection against certain infections, it would be unfortunate if its uncontrolled application in influenza should result in prejudicing critical and scientific minds against it."

The authors describe an evolution in their methods, which involved first coughing and then later nebulizing biological aerosols, first collecting by gravitational settling and then later drawing by air onto a petri dish, first assessing filter performance and then later evaluating the impact of leakage around the edges of a mask. Their final conclusions were:

- Gauze masks can prevent inhalation of a "certain amount of bacteria-laden droplets."

- Mask performance depends on the number of layers and the "fineness of mesh" of the gauze.

- When they were able to demonstrate a "useful filtering influence" breathing became too difficult and leakage occurred around the mask.

- Leakage lowered mask efficiency to 50 percent, regardless of number of layers and fineness of mesh.

- "Masks have not been demonstrated to have a degree of efficiency that would warrant their compulsory application for the checking of epidemics."

Today there is a greater variety of materials from which to fashion masks, but the same problems noted by Kellogg and MacMillan apply. As well, the data indicate that SARS-CoV-2 (and influenza, as well) is not transmitted solely by large droplets, but rather by inhalation of small infectious particles near a source.

JH & VR: "Osterholm claims that 'in the earliest days of this pandemic we knew that breathing air would be the main way the virus would be transmitted'. We knew no such thing then, and we don't know it now … Few if any pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic patients show significant lower respiratory tract shedding, which would be required for breathing to be a transmission vector.'"

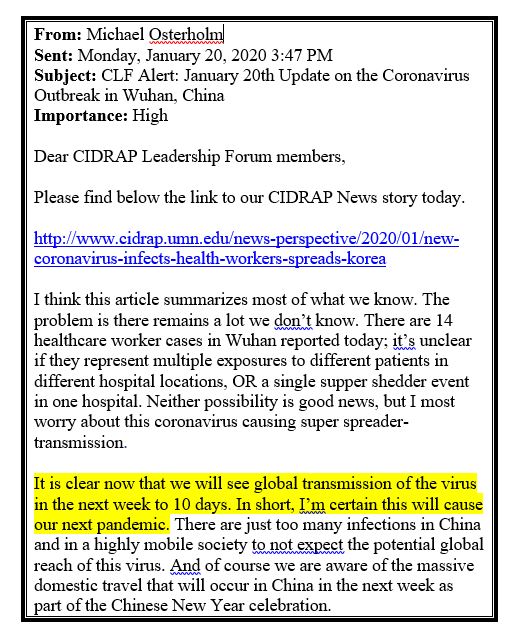

MTO: I was one of the first to recognize and declare the pandemic po tential of this situation. I shared my certainty in a Jan 20 email to the CIDRAP Leadership Forum—a group of businesses that CIDRAP consults with—preceding the WHO's declaration of a pandemic by over a month and a half (see screenshot at right, with the key text highlighted). I made that declaration based on publicly available data at the time pointing to the very efficient transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2. In fact, SARS-CoV-2 still appears to be more transmissible than SARS-CoV (the virus that causes SARS) and the 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Based on my previous expertise with respiratory illnesses such as influenza, this level of dynamic transmission suggests that the simple act of breathing air can play a major role in spreading the virus.

tential of this situation. I shared my certainty in a Jan 20 email to the CIDRAP Leadership Forum—a group of businesses that CIDRAP consults with—preceding the WHO's declaration of a pandemic by over a month and a half (see screenshot at right, with the key text highlighted). I made that declaration based on publicly available data at the time pointing to the very efficient transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2. In fact, SARS-CoV-2 still appears to be more transmissible than SARS-CoV (the virus that causes SARS) and the 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Based on my previous expertise with respiratory illnesses such as influenza, this level of dynamic transmission suggests that the simple act of breathing air can play a major role in spreading the virus.

JH & VR: "The closest thing we have… to a relevant RCT is the paper The First Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial of Mask Use in Households to Prevent Respiratory Virus Transmission: This was an Australian study for influenza control in the community, but not during a pandemic, and without any enforcement of compliance (such as would be provided by a mask mandate). It stated that 'observational epidemiologic data suggest that transmission of viral respiratory infection was significantly reduced during the SARS epidemic with the use of face masks as well as other infection control measures' and 'in an adjusted analysis of compliant subjects, masks as a group had protective efficacy in excess of 80% against clinical influenza-like illness.' However, the authors noted that 'we found compliance to be low, but compliance is affected by perception of risk. In a pandemic, we would expect compliance to improve. In compliant users, masks were highly efficacious.'"

MTO: The study cited here does not directly assess influenza control in the community—nor does it assess cloth face coverings. Rather, it looked at whether or not masks interrupted transmission among household members. The researchers recruited 286 adult family members of children who showed up to emergency departments with influenza-like illness. Recruited family members were randomly assigned surgical masks, non-fit-tested P2 masks (the Australian equivalent to an N95 respirator), or no masks.

It is important to clarify that the effectiveness of medical masks—not cloth face coverings—was being evaluated in this study. Also, although compliance seemed to play a role in their results, the authors concluded the following:

"Using intention to treat analysis, we found no significant difference in the relative risk of respiratory illness in the mask groups compared to control group. However, compliance with mask use was less than 50%. In an adjusted analysis of compliant subjects, masks as a group had protective efficacy in excess of 80% against clinical influenza-like illness. The efficacy against proven viral infection and between P2 masks (57%) and surgical masks (33%) was non-significant." [emphasis added]

JH & VR: "Osterholm also quotes from a report from the Usher Network for COVID-19 Evidence Reviews (UNCOVER), but failed to quote from the relevant section, which actually concluded that 'homemade masks worn by sick people can reduce virus transmission by mitigating aerosol dispersal. Homemade masks worn by sick people can also reduce transmission through droplets. By reducing the number of droplets reaching surfaces, homemade masks can reduce the risk of transmitting or acquiring COVID19 through reducing environmental (surface) contamination'."

MTO: The "relevant" section referred to in the UNCOVER report features two references. Both use schlieren imaging to visualize airflow. It is important to note that schlieren imaging does not gauge particle emission—meaning it reveals nothing about aerosol emission or inhalation. These kinds of images were used by early aerobiologists when they lacked the kinds of instruments we have today to measure particle size and concentration from subjects.

The first referenced study assessed the impact surgical masks and N95 respirators had on airflows. Seeing as these are medical masks, their performance cannot be directly extrapolated to cloth face coverings, which were not evaluated in this study. Additionally, their primary conclusions relate to the effectiveness of masks as source control when the wearer coughs. This is largely irrelevant to COVID-19, since sick people who are coughing should not be out in public.

The second study cited in this section of the UNCOVER report is a prepublication that also used schlieren imaging to look at airflow patterns when wearing a mask, cloth face covering, or face shield. The authors concluded:

"Hand-made masks…generate significant leakage jets that have the potential to disperse virus-laden fluid particles by several metres. The different nature of the masks and shields makes the direction of these jets difficult to be predicted, but the directionality of these jets should be a main design consideration for these covers. They all showed an intense backward jet for heavy breathing and coughing conditions. It is important to be aware of this jet, to avoid a false sense of security that may arise when standing to the side of, or behind, a person wearing a surgical, or handmade mask, or shield."

JH & VR: "However, he appears not to be aware that this issue has been well studied and measured by aerosol scientists and fluid dynamics experts. In particular, Schlieren imaging shows that during normal breathing nothing escapes around the sides of a cloth mask. Even during coughing, a cloth mask dramatically decreases the radius of the droplet cloud and the number of droplets it contains. There is still a lot we don't know about the relative impact on transmission of the different particle sizes released during breathing and speaking, and about exactly how much of each size different types of mask can filter, but we do know that cloth masks block many particles effectively."

MTO: The study using schlieren imaging is the same prepublication mentioned just above this, which has considerable limitations. To begin, air absolutely does escape around a cloth face covering. Air has to go somewhere and takes the path of least resistance. This is what makes fit a critical part of respiratory protection. Table 6b of the referenced study indicates that airflows generated during quiet—or normal—breathing while wearing a cloth face covering generated a backward jet. This finding supports the authors' suggestion that people should be made aware of this jet to avoid a false sense of security that may arise when standing behind a person wearing a cloth face covering. In general, the authors conclude that "the hand-made mask was least effective in stopping air leakage."

This research illustrates that it's important to think about air—and particle—emission in many directions from a facepiece. However, it offers no data about the impact of cloth face coverings on particle emission. Without particle data, it's only possible to conjecture about the size and concentration of particles that make it through the filter or around the edges.

Final thoughts

It is unfortunate that my and CIDRAP's position on cloth face coverings is being mischaracterized by not only those who are staunchly anti-mask but also by pro-mask groups. I find it most fitting to conclude this commentary with this piece from a Jul 2 FiveThirtyEight story titled, "The science of mask-wearing hasn't changed. So why have our expectations?":

The good news is that there's more agreement than disagreement on where to start. Just look at Osterholm and Howard…they hold similar positions on one issue: They both wish the CDC would have given the public the nuanced information about masks back in March and trusted them to understand it. Granted, that might mean presenting the public with a complex message, such as: "We don't know how well cloth masks work, so distancing should come first, but masks are likely to work to some extent and not everyone can distance themselves." That's a mouthful and harder to fit on a bumper sticker than "yes, you should," or "no, you shouldn't." But it comes down to what builds trust more: certainty or honesty?

I can assure you that we here at CIDRAP will always stick with honesty.