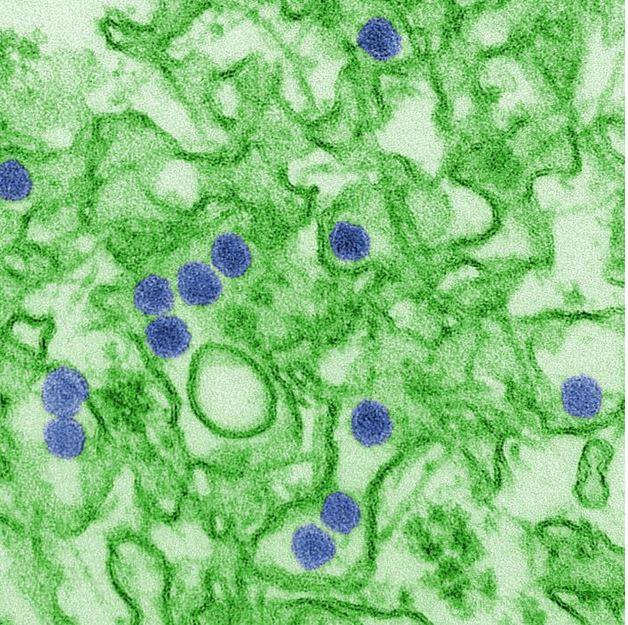

Since an outbreak of Zika began in Brazil in 2015, clinicians have documented subsequent cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) in some infected patients.

A study published yesterday in JAMA Neurology compared the presentation of GBS in patients with or without confirmed Zika infections in Puerto Rico in 2016 and found that patients with GBS and Zika had more severe symptoms, including facial weakness, abnormal facial sensation, and protein in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) during the acute phase of the disease.

GBS is a post-infectious, autoimmune disorder, characterized by damage to the peripheral nerves resulting in weakness and poor reflexes. Several studies have linked Zika to an increase risk for developing GBS, and though incidence is still low, countries with large Zika outbreaks have reported a spike of GBS cases in the months following a wave of Zika activity.

Serious neurologic problems, need for ICU

To conduct the study, researchers compared 123 Puerto Rican patients with GBS, testing for Zika with real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction at initial symptom onset and during a 6-month follow-up. A total of 71 patients included in the study had evidence for Zika, and 36 did not.

During the acute clinical phase, the GBS patients with Zika were more likely to be admitted to intensive care and require ventilation. Overall, their clinical presentation was more severe than GBS patients without Zika.

Zika GBS patients had the following rates of these conditions compared with GBS patients without Zika:

- Facial weakness, 62.0% vs. 27.8%

- Difficulty swallowing, 53.5% vs. 25.0%

- Shortness of breath, 46.5% vs. 25.0%

- Facial paresthesia, 18.3% vs. 2.8%

- Elevated CSF protein, 94.2% vs. 71.9%

- Admission to intensive care, 66.2% vs. 44.4%

- Need for mechanical ventilation, 53.6% vs. 26.1%

"At 6 months, GBS patients with Zika infection were more likely to have excessive or inadequate tearing [under- or overproduction of the tear ducts], difficulty drinking, and pain," Emilio Dirlikov, PhD, the lead author of the study and a researcher with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told CIDRAP News. "Clinicians should be aware of these symptoms to diagnose GBS patients and promptly initiate patients on appropriate treatment."

The study also revealed a curiosity about Zika symptoms: The vast majority (80%) of GBS patients with Zika were also more likely to complain of Zika symptoms, while 80% of people with Zika who do not develop neurologic symptoms also never develop Zika-related symptoms.

Despite more clinically severe GBS, patients who tested positive for Zika had no higher incidence of disability at 6 months follow-up, but they were more likely to report cranial neuropathy.

Questions for future research

Dirlikov said the study's most important implication for future investigations is determining the specific risk factors for developing GBS following Zika virus infection.

"Research should examine the specific disease process by which Zika may trigger GBS, including investigating antigens that are specific to or overexpressed in cranial nerves, given clinical features identified in this investigation," he said.

"Finally, continued research should investigate the increased number of GBS patients during Zika virus epidemics as opposed to other triggers for GBS, including flaviviruses such as dengue virus."

See also:

May 21 JAMA Neurol study