In a development that could greatly improve the tracking of drug-resistant malaria, a research team today reported two new tests for the trait, one that could be used to streamline detection of resistance in patients and another that could be used in labs to explore resistance and assist malaria drug development.

The first new technique is poised to replace the current test for resistance to artemisinin, the world's most potent tool for fighting malaria. Resistance to the drug was confirmed at the Cambodia-Thailand border in 2009, spurring global health efforts to preserve the drug's usefulness.

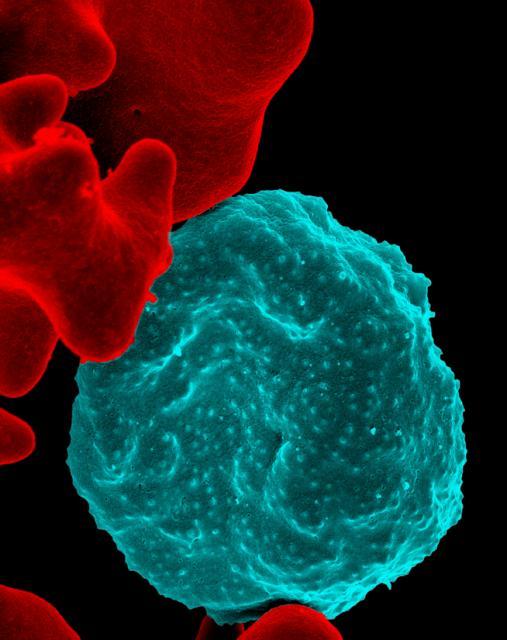

The current test for resistance is a labor-intensive process that requires malaria patients to be hospitalized so clinicians can test their blood every 6 to 8 hours for 2 or 3 days after they begin taking the drug. Researchers from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), along with collaborators from France and Cambodia, reported their findings yesterday in an early online edition of Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Both tests are designed to mimic parasite exposure to the drug in patients undergoing treatment for malaria. The first test, which can be used in the field, produces a result in 72 hours and predicts if the patient has a slow-clearing, drug-resistant form of the parasite. The procedure is conducted on blood taken from a malaria patient at the same time he or she receives the first dose of artemisinin-based combination drug therapy.

In the second test, technicians adapt parasites from a malaria patient's blood sample onto a lab culture, synchronize the parasite life stages, then apply artemisinin only to those that are 3 hours old or younger. The group wrote that the second test will probably be most useful to define the molecular basis of artemisinin resistance and to screen new drugs.

In another important finding from the study, researchers used the test to detect artemisinin-resistant parasites for the first time in northern and eastern Cambodia.

The group concluded that the tests could help monitor the worsening of resistance in areas where it is already entrenched, such as western Cambodia, and track its spread or emergence elsewhere in the greater Mekong subregion. They also said the techniques could be used at sentinel sites in areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, where artemisinin resistance would be particularly devastating.

In an editorial in the same issue, Carol Hopkins Sibley, PhD, professor of genome sciences at the University of Washington who is scientific director for the Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network, wrote that the researchers are reporting two important advances.

"With these simple methods in place, rapid tracking of the geographical and temporal changes in artemisinin resistance will be feasible in many sites," she wrote, adding that the information will allow policymakers to design effective responses to battle resistance, which could prolong the usefulness of artemisinin-based combination therapy.

Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, et al. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2013 Sep 11 [Abstract]

Sibley CH. Tracking artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. (Editorial) Lancet Infect Dis 2013 Sep 11 [Abstract]

See also:

Sep 10 NIAID press release