Mar 28, 2012 (CIDRAP News) – In a set of articles published today in Nature, influenza experts say global flu surveillance—especially in poultry and swine—is sorely lacking and needs a major overhaul to make it more sustained, timely, and representative.

In an editorial, a news report, and two commentaries, experts make the case that current surveillance efforts are far too sparse, erratic, and crisis-driven and that they suffer from a geographic imbalance.

"Imagine a global weather and climate forecasting system that collects data regularly in just a handful of countries, and takes measurements elsewhere only during extreme weather events," says the editorial. "That is what today's global flu-surveillance system mostly looks like."

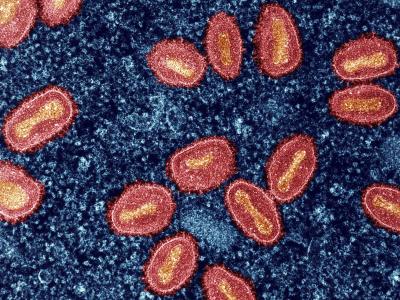

The gaps in flu surveillance are well known, but they are getting renewed attention following the creation in labs of H5N1 strains that can spread in mammals, the editors said in a reference to unpublished studies by teams at Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands and the University of Wisconsin. A US biosecurity advisory board recommended in December that the full details of the studies not be published.

The centerpiece of the Nature articles is an analysis piece by reporter Declan Butler. He notes that flu surveillance is important not only for detecting pandemic threats, but also for spotting outbreaks, monitoring viral evolution, understanding factors that enable viruses to spread, and maintaining the effectiveness of animal vaccines and diagnostics.

Looking for trends, Butler examined the records of all non-identical sequences from all types of avian and swine flu deposited in the US National Center for Biotechnology Information's Influenza Virus Sequence Database between 2003 and 2011.

To summarize the "dire state" of animal flu surveillance, Butler writes that the world had 21 billion poultry in 2010, but only about 1,000 flu sequences from 400 avian virus isolates were collected, and many countries that have billions of poultry contributed few or none of those sequences.

The number of avian sequences deposited in the database generally rose between 2003 and 2010, but then sagged, he found. Meanwhile, the number of pig sequences stayed fairly flat from 2003 to 2010 before surging last year.

An additional problem is that years can pass between the collection and sequencing of isolates, Sylvie van der Werf, PhD, of the Pasteur Institute in Paris told Nature. Reasons include lack of funding and the disinclination of many researchers to share their sequences before publishing their findings.

Butler also found that almost all sequences come from "a handful" of countries, led by the United States and China.

Summing up the findings, the editorial states, "From 2003 to 2011, most countries collected few or no sequences, and genetic surveillance of flu in pigs was and is almost non-existent."

Flu experts say the situation could be rapidly improved by setting up, in the countries and regions at highest risk, a network of sentinel sites to collect viruses and sequence them quickly, according to Butler's report. But international leadership is needed, and no global body has overall responsibility for flu surveillance, he says.

In a commentary, Jeremy Farrar, DPhil, who works at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, contends that one way to improve flu surveillance is to move a share of the relevant expertise and technology from the developed world to the developing countries that are most threatened by H5N1 and other emerging diseases.

"I believe that we have to bring some of the huge investment by the developed world in genomics, technology and training to affected countries in Asia and elsewhere," writes Farrar, who is in the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit at the hospital. "In this way, surveillance, analysis, of samples, and—crucially—the public health and clinical research response can be conducted in the same place, making the process faster and more flexible in dealing with rapid developments.

"It would require a transfer of technology, prolonged exchange of scientists and a sustained commitment to investment and training locally—along with an equitable sharing of the benefits of the research," he adds.

Farrar remarks that today, 8 years after Vietnam's first human H5N1 case, too few H5N1-endemic countries have access to vaccines or intravenous antiviral drugs. And in a reference to the reports of lab-modified H5N1 viruses that can spread in mammals, he adds that "scientists like us in endemic areas" are still waiting to learn about the mutations that led to increased transmissibility.

In a fourth article, four experts from four different countries offer brief suggestions about ways to improve monitoring of H5N1 viruses. For example:

Yi Guan, MD, PhD, of Shantou University and Medical College and the University of Hong Kong in China, calls for more active surveillance of ducks in affected areas, since 70% of the world's ducks are raised where H5N1 is endemic.

Richard Webby, PhD, of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, says a good first step to improve swine surveillance—now scattered among universities, industry, and government agencies—would be to increase coordination by establishing a centralized database.

Butler D. Flu surveillance lacking. Nature 2012 Mar 29;483(7391):520-2 [Story]

Farrar J. H5N1 surveillance: shift expertise to where it matters. (Commentary) Nature 2012 Mar 29;483(7391):534-5 [Article]

Guan Y, Webby R, Capua I, Waldenstrom J. How to track a flu virus: four experts pinpoint ways to improve monitoring of H5N1 influenza in the field. (Commentary) Nature 2012 Mar 29;483(7391):535-6 [Article]

Nature editors. Must try harder. (Editorial) Nature 2012 Mar 29;483(7391):509-10 [Article]