Contrary to popular belief, plague's decimation of Europe's population began thousands of years before the major outbreaks of the Middle Ages (14th century), DNA from Stone-Age bones and teeth suggests.

A team led by University of Copenhagen researchers in Denmark used population-scale ancient genomics to infer ancestry, social structure, and pathogen infection in 108 farmers from the Neolithic (late Stone Age) period buried in eight megalithic (large stone) graves in Sweden and a cist (small stone coffin-like box) in Denmark. They also reconstructed four six-generation pedigrees, the largest of which was made up of 38 members with a patrilineal social organization.

The results were published yesterday in Nature.

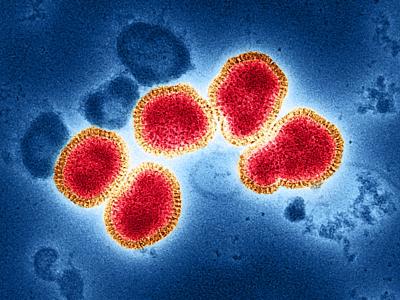

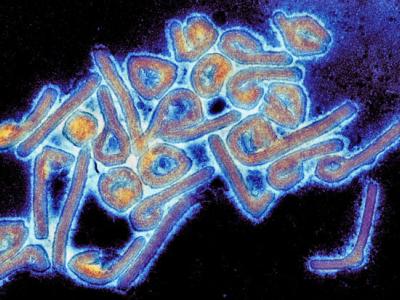

Plague, which is associated with bacteria-carrying fleas and rodents and can spread from person to person via respiratory droplets, killed up to half the European population, which equates to as many as 200 million people. It is characterized by lymph-node swellings, fever, muscle aches, and weakness and is caused by Yersinia pestis bacteria.

"In the period between 5,300 and 4,900 calibrated years before present (cal. BP), populations across large parts of Europe underwent a period of demographic decline," the study authors noted. "However, the cause of this so-called Neolithic decline is still debated," with experts disagreeing on whether it was caused by an agricultural crisis, war, or an early form of the plague.

Plague found in 17% of remains

Plague was detected in the 5,000-year-old DNA of at least 17% of the sampled population across large geographic distances. Analysis of one family revealed at least three distinct infection events over roughly 120 years and found direct genomic evidence of the practice of mating outside of a social group in a woman buried separately from her brothers.