The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is monitoring nine more workers who may have been exposed to anthrax bacteria in its labs, amid new revelations about the potential contamination that triggered its investigation.

Yesterday the agency announced that it was monitoring 75 people after samples of Bacillus anthracis weren't adequately inactivated before a high-containment lab prepared them for teams working in lower-containment labs. The CDC, however, is now monitoring 84 employees, according to Benjamin Haynes, senior press officer for the division of public affairs' infectious disease team.

So far none of the potentially exposed employees have shown any signs or symptoms, he said.

As of yesterday afternoon, the CDC's occupational health clinic had seen 54 of the 84 employees. Among them, 32 started or continued to take ciprofloxacin, 20 started taking doxycycline, and 2 declined oral antibiotics.

Postexposure prophylaxis after possible exposure to B anthracis, the bacterium that causes anthrax, consists of oral antibiotics and anthrax vaccination. Anthrax-causing spores in the body generally take 1 to 6 days to activate but can remain in the body and activate as late as 60 days, so the antibiotic course is generally 60 days for those who may have been exposed.

Anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA), which can be given under special protocols for emergency use in adults ages 18 to 65, is administered in five doses over 18 months.

Haynes said 27 employees have started their vaccinations, 19 declined to be vaccinated, and 8 are still considering vaccination.

New method goes awry

In other developments, Paul Meechan, PhD, MPH, director of environmental health and safety compliance at the CDC, said the problem that raised alarms about potential exposure arose from testing a new way to kill B anthracis with chemicals instead of radiation, the New York Times reported yesterday.

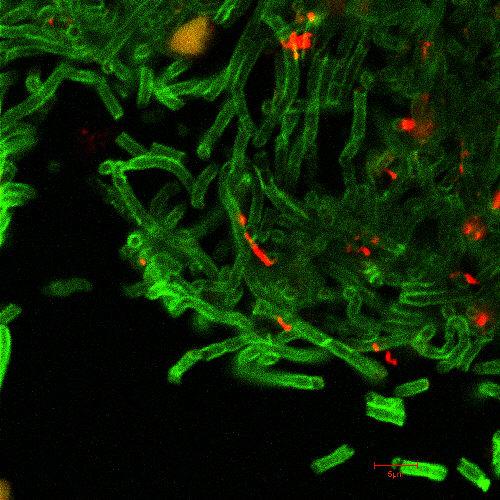

In research centers, high-containment labs often kill or inactivate pathogen samples to ease work with the organisms in lower-containment labs, a step that often helps streamline the experiments.

Meechan said that, after chemical treatment, the bacteria were put on agar plates and incubated for 24 hours, according to the Times. The scientists assumed the bacteria were dead after no colonies grew. "It didn't work as well as they thought," Meechan said.

Six days later, when they went to dispose of the agar plates, scientists saw B anthracis colonies on them, indicating that some of the bacteria survived the chemical inactivation process, Meechan told the Times.

Though lab research often involves the Sterne strain, which can infect but can't keep reproducing, the CDC experiments used the more lethal Ames strain, because the experiments in the labs were geared toward new ways of detecting it, Meechan said.

See also:

Jun 19 New York Times story

Jun 19 CIDRAP News story "CDC probes anthrax exposure at its research labs"