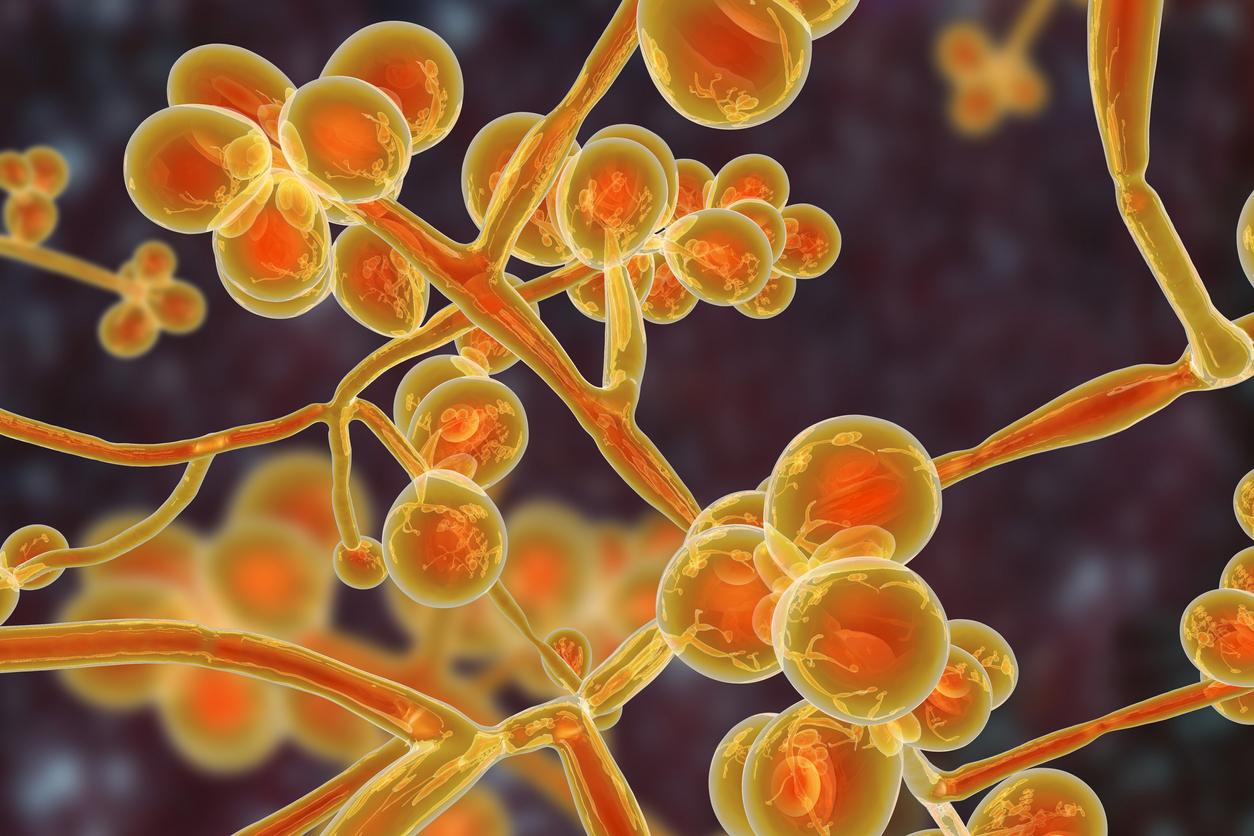

New surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that US healthcare facilities have seen an alarming increase in the spread of Candida auris.

The data, published today in the Annals of Internal Medicine, shows that clinical cases of the multidrug-resistant yeast rose by 59% in 2020 and 95% in 2021, after several years of slow but steady increases. The number of states experiencing clinical cases also rose significantly from 2019 to 2021. And resistance to first-line treatment is rising.

The CDC says that while many factors are at play, including the difficulty of containing C auris once it gets into a healthcare facility, the timing of the increase suggests that COVID-19 pandemic-related strains on the healthcare system likely played a role.

"There were a lot of challenges before COVID, and those were probably just magnified by turnover of staff, the lack of supplies, people being tired…and just being stretched very thin," CDC epidemiologist and lead study author Megan Lyman, MD, told CIDRAP News.

Sharp spike in clinical cases, colonization

First detected in the United States in 2016, C auris was slowly spreading across the country prior to the pandemic, climbing from 53 cases in 2016 to 330 in 2018 and 476 in 2019. Annual clinical cases then rose by 756 in 2020 and 1,471 in 2021.

The initial cases were identified in 10 states but were primarily in New York and New Jersey. The pathogen is now in 27 states, with 8 states reporting their first case in 2020—the highest number of new states affected in 1 year—followed by 3 more in 2021.

The CDC was concerned about C auris even before the first US case was identified, for a number of reasons. Since it was discovered in Japan in 2009, C auris has shown resistance to all three classes of antifungal medication and the ability to cause invasive infections in some of the most vulnerable patients, including those with indwelling devices like catheters and ventilators. Mortality rates range from 30% to 40%.

Furthermore, C auris likes to colonize patients' skin and transmits easily in healthcare facilities, spreading from patients to bed rails, hospital curtains, and floors—where it can persist for up to a month. And it's proven difficult to eradicate with standard hospital disinfectants. Once it was clear that it had arrived in the United States, the CDC named it an urgent threat.

Speaking on a recent episode of the CIDRAP podcast Superbugs & You, Tom Chiller, MD, chief of the CDC's Mycotic Diseases Branch, said the combination of easy transmission, drug resistance, and ability to cause invasive, deadly infections makes C auris different from other fungal pathogens that cause infections.

"It's got all the characteristics of a hospital-acquired bacteria," Chiller said. "So we really had to change our dogma about how we deal with this fungal organism."

The data from state health departments, which are required to notify CDC of clinical C auris cases, show that a total of 3,270 cases were reported through 2021, along with 7,413 screening cases. The report notes that many US health departments began increasing screening efforts after identifying clinical cases in healthcare facilities, which led to a jump in screening tests and a 209% increase in the identification of colonized patients in 2021.

The number of screening cases is likely higher, the report notes, because not all healthcare facilities are screening at-risk patients. Although many colonized patients don't develop C auris infections, colonization can present a risk for further spread.

How COVID-19 contributed to rise in C auris cases

The data also shows that long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), where patients with serious medical conditions receive ongoing care, remain the primary facilities impacted by the pathogen.

"These high-acuity post-acute care facilities are where we're seeing most cases and most transmission, and that's the reason why a lot of the prevention and control efforts are focused on these types of facilities," Lyman said.

But the pandemic also saw outbreaks of C auris in acute care hospitals as well. In a CDC report published in July 2022, C auris was one of eight specific infections that rose significantly in US hospitals in 2020, with a 60% increase compared with 2019.

The agency attributed those outbreaks in part to pandemic-related staffing shortages; hospital staff who were normally responsible for standard infection prevention and control (IPC) strategies that can help reduce the incidence of pathogens like C auris and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus were diverted to COVID care. In addition, hospitals were filled with severely ill, intubated COVID patients susceptible to infections with these pathogens.

Our hope is to try and share this information with others so that they can see how bad it could be if they don't act now.

Lyman noted that other pandemic-related factors also played a role. For example, a CDC investigation of a C auris outbreak at a Florida hospital in July 2020 concluded that the multiple layers of gowns and gloves worn by healthcare staff to protect against COVID-19, and repeated doffing and donning of secondary layers, may have led to contamination of base layers and contributed to C auris transmission. At other hospitals, strategies to deal with shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) may have unwittingly caused transmission.

"They were worried about running out of PPE," she said. "So they were using one gown and glove for multiple patients or multiple patient encounters and I think that that may have also contributed to some spread."

Rising resistance

On top of the spike in clinical C auris cases, antifungal susceptibility testing by the CDC Antibiotic Resistance (AR) Lab Network found that 86% of isolates tested in 2020 were resistant to azoles, with resistance rising by 7% from 2019 to 2020, and 26% were resistant to amphotericin B. High resistance to azoles was common in all US regions except the Midwest.

Most concerningly, the number of C auris cases resistant to echinocandins—the first-line treatment for all invasive Candida infections—tripled in 2021 compared with 2020 (rising from 3 to 19), while the number of pan-resistant cases rose from 6 to 7. Investigation of two independent outbreaks of echinocandin- and pan-resistant C auris among patients with shared healthcare exposures found that none had previous exposure to echinocandins, which suggests the cases were healthcare-associated.

Lyman said that while the increase in C auris cases highlights the need for better screening and IPC strategies to limit the spread of the pathogen, there are several examples of healthcare facilities that have been able to control transmission and prevent major outbreaks from occurring. She and her CDC colleagues are hoping that this report will prompt hospital officials to start screening at-risk patients and boosting IPC practices before they even identify a case, so that they can have practices in place to mitigate spread.

"Our hope is to try and share this information with others so that they can see how bad it could be if they don't act now," she said.