A new analysis of the H7N9 virus from the first known case in China's ongoing outbreak found that signs of antiviral resistance weren't flagged by regular sensitivity testing, which could prevent detection and allow resistant strains to spread, a research team reported today.

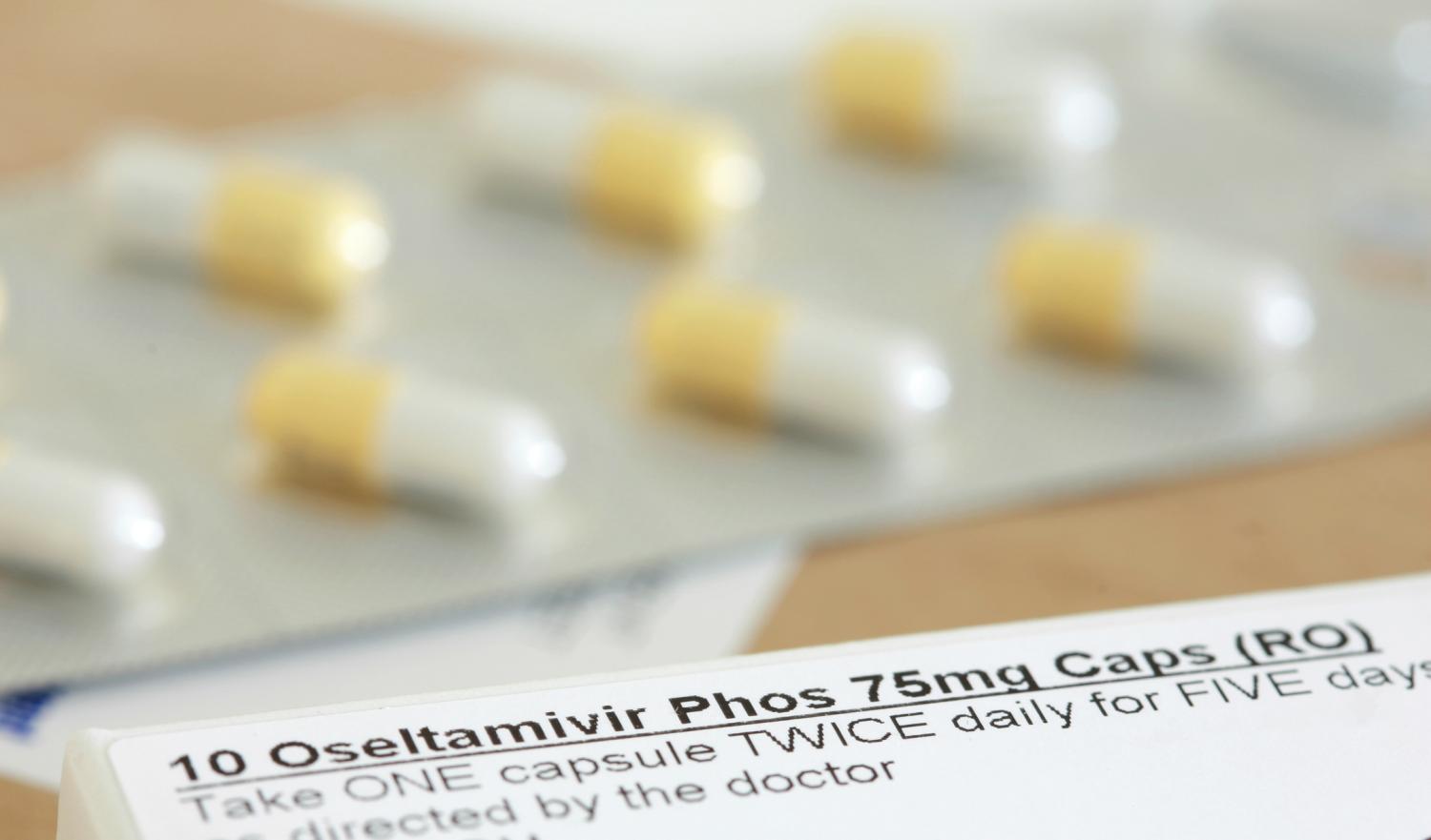

A number of the viruses the team grew from the strain obtained from a patient in Shanghai had a mutation linked to resistance to the neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir, which are considered the frontline treatments for the often-severe H7N9 infections. Resistance to M2 ion channel blockers, another class of antivirals, has already been found in H7N9 isolates.

Researchers from China, Hong Kong, Australia, and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis reported their findings in the latest issue of mBio, the online journal of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM).

The group's worrisome findings about H7N9 antiviral resistance echo other findings reported from both clinical settings and lab studies. In the middle of April, about 2 weeks after the outbreak emerged, one of the first genetic analyses of H7N9 viruses from the initial confirmed cases found a neuraminidase inhibitor resistance marker in one of the three strains.

In early May a clinical report on four severely ill H7N9 patients treated at a Shanghai hospital aired early suspicions about oseltamivir failures in two of the patients. Later that month a team looking for evidence of antiviral resistance in 14 hospitalized Shanghai patients who received oseltamivir found a known resistance marker in those who didn't respond to treatment and had a poor prognosis.

The authors of today's study initially used an antiviral susceptibility test that gauges the activity of the neuraminidase enzyme to examine the H7N9 strain, which suggested that it was sensitive to the drugs. However, when they took a closer look with genetic analysis, they found that their sample contained two different H7N9 variants. About 35% of the isolates in the sample carried the R292K mutation, which makes them resistant to neuraminidase inhibitors.

Virologists have seen the same mutation in resistant seasonal H3N2 strains and also in H1N9 viruses tested in lab settings.

Robert Webster, PhD, a virologist at St Jude's and the study's corresponding author, said in an ASM press release today that the enzyme-based tests yielded a misleading result because functioning wild-type enzymes masked the presence of the nonfunctioning mutant enzymes.

He said findings raise concerns about what could happen if the H7N9 virus gains the ability to easily spread from person to person. "What do we have to treat it with until we have a vaccine? Oseltamivir," he said. "We would be in big trouble." He added that the R292K mutation puts the options in jeopardy.

Webster and his colleagues noted in the study that the antiviral resistance characteristic can be a burden for flu viruses and that the fitter, wild-type H7N9 might edge out the resistant strains. In the absence of a drug like Tamiflu (oseltamivir), it seems unlikely that the resistant viruses would acquire epidemic characteristics, they wrote.

Webster said in the statement that a great need is additional drugs that target different sites in the influenza genome. "There are some [drugs] in the pipeline, but they are still under testing at the moment," he stated. "We'd better get some vaccine seed stocks up and ready. The antiviral option for controlling H7N9 isn't too good."

Yen HL, McKimm-Breschkin, Choy KT, at al. Resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors conferred by an R292K mutation in a human influenza virus H7N9 isolate can be masked by a mixed R/K viral population. mBio 2013 (published online Jul 16) [Full text]

See also:

Jul 16 ASM press release

Apr 12 CIDRAP News story "H7N9 genetic analysis raises concern over pandemic potential"

May 3 CIDRAP News story "No new H7N9 cases as clinical, treatment details emerge"

May 28 CIDRAP News story "Researchers find easy development of H7N9 Tamiflu resistance"