May 27, 2005 (CIDRAP News) – The plot of the world's latest pneumonic plague outbreak echoes with history.

Like a 19th-century American gold rush, news of the discovery of diamonds in a remote northeastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in November 2004 sparked an influx of adventurers hoping to strike it rich.

Like boomtowns of the past, a city of 7,000 people mushroomed around the mine, which lies deep in the forest, an hour's walk from the town of Zobia.

Then the plague arrived, felling miners and mothers alike.

What worries Eric Bertherat, MD, MPH, MSc, a World Health Organization (WHO) doctor whose team helped stop the outbreak, is history's tendency to repeat itself. Bertherat said in a recent phone interview from Geneva that he is certain the conditions that led to 124 cases of pneumonic plague and 56 deaths earlier this year will resurface in the DRC—probably soon.

And despite the focus on plague as a potential bioterror weapon in the developed world, it remains to be seen how the recent attention will help address this age-old problem.

A peculiar outbreak

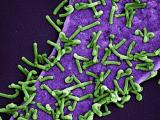

Plague is endemic in parts of the DRC's Ituri region, but this outbreak was unusual, Bertherat said. The Zobia area is 400 kilometers from previous known plague-endemic areas, and all the cases were pneumonic. Overall, only about 2% of plague cases are pneumonic; most are bubonic, spread by rodents carrying infected fleas. People can contract pneumonic plague by inhaling the pathogen, Yersinia pestis, in aerosol form.

When it heard about a serious outbreak, the WHO sent a team to Zobia. Bertherat and his colleagues flew to the DRC on Feb 19, heading for the Ituri region, which has seen chronic and dramatic humanitarian crises since 1998. A United Nations helicopter ferried them partway; then the team hiked to the camp.

"It was like a slum in the middle of the forest," he said. People had to carry clothes, batteries, and other goods from Zobia. There was no clean drinking water.

Panic had made the outbreak harder to control, he said. When miners fell sick, hundreds of people fled the site, which sparked fears that the outbreak might spread widely. Some died along forest trails. Initial reports suggested there might be hundreds of plague cases. That number dwindled to 124 confirmed, suspected, or probable cases, with 56 deaths.

Investigators found myriad rodents near the mining camp, but no bubonic plague.

"The index case was imported from somewhere else," Bertherat said. The victim might have been a miner from a plague-prone part of the Ituri region.

The pull of diamonds was so powerful that it was difficult to get miners to take preventive medication, and an isolation ward that was set up in the mine camp sat empty. No one wanted to stay there when they could be finding diamonds.

The plague spread beyond the mining camp, claiming the life of a young mother from Zobia. After a long scramble, doctors found a 4-month supply of milk for her 6-month-old baby and gave it to the father, Bertherat said.

The outbreak smoldered for 11 weeks. Healthcare workers at the scene knew that gentamicin works well and they used it quickly, helping limit the outbreak. The onset of the dry season also caused the mine camp population to dwindle to about 2,500 people, because water is necessary for diamond mining.

In addition, some people who felt sick and fled might have been suffering from something other than plague.

"There were many reasons for coughing," Bertherat said. Without sufficient investigation, "It was difficult to say if it was the flu or the plague."

Despite the return of the rainy season in March, the DRC has not seen any new plague cases so far, he said.

Anticipating more episodes

The WHO team left Zobia March 12, nearly at the end of the outbreak. They took something valuable with them: about 120 blood and sputum samples from patients.

The samples were shipped to eight laboratories in several countries to bolster research on up to 15 different plague diagnostic tests, Bertherat said. The samples enable labs to compare testing techniques. Sensitive rapid field tests are the key to stopping outbreaks.

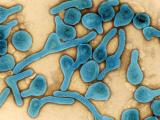

Bertherat, who worked in the same DRC province in 1999 on a Marburg hemorrhagic fever outbreak, predicted the plague would recur there soon.

The Ituri region is the most active focus of human plague in the world, he said. He worries that the next outbreak will find footing in a big city in the region. For example, the city of Bunia now has a refugee camp teeming with 12,000 people, many of them children.

"Sanitary conditions have decreased" in the region, he said. "We try to sound the alert, but in terms of plague . . . there is no interest by the donors," meaning wealthy countries.

Some people worry that the developed world's interest in bioterrorism dilutes attention to natural outbreaks. However, one expert says concerns about terrorist-caused outbreaks can lead to responses relevant to natural outbreaks as well.

Dual-purpose research

Plague is rare in the United States, with only 20 cases recorded between 1999 and 2003, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Although the nation conducts some plague surveillance and research, the focus is chiefly on the potential for bioterrorism, C.J. Peters, MD, director of biodefense and professor of pathology, microbiology, and immunology at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, told CIDRAP News. Yet research on tests, vaccines, and treatments can serve both interests, in his view.

"People are working hard for rapid tests," Peters said. Beyond the problem of developing them, diagnostic tests pose challenges in production, distribution, and user education.

"These rapid tests are frequently not economically viable," he said. Bioterrorism preparedness efforts could bolster that process: if a good, reasonably priced rapid test for plague is created, it could be stockpiled, he added.

Another area with potential for crossover is vaccines, Peters said. The US Army has produced a plague vaccine, although it hasn't yet been tested.

In addition, experts hope to deepen the pool of existing antibiotics used to treat plague. Gentamicin works well, Peters said, but having other treatments is important to biodefense interests.

Perhaps because plague is so rare in the United States, there is a tendency to minimize its impact, according to Peters. "It's important that people realize that plague is a worldwide problem," he said.

See also:

Feb 18, 2004, CIDRAP News story "Pneumonic plague outbreak in Congo sparks WHO response"

http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/bt/plague/news/feb1805plague.html

CIDRAP overview of plague

https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/plague