Oct 25, 2005 (CIDRAP News) The deaths of nine people in Idaho this year are being investigated as possible cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), a rare, fatal brain-wasting illness.

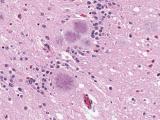

The unusual number of possible cases has prompted widespread interest and concern. CJD, a disease involving infectious proteins called prions, progresses rapidly and is usually fatal within a year of onset. It differs from the human equivalent of mad cow disease, which is known as variant CJD (vCJD). CJD does not spread among people through ordinary contact, but it may be spread through contaminated surgical instruments or implants of infected tissue.

The usual incidence of CJD is about one case per million people annually. Idaho, with its 1.3 million people, typically has zero to three deaths a year, said Tom Machala, RN, MPH, division director of Communicable Disease and Prevention in Idaho's South Central District Health Department in Twin Falls.

The cases were suspected initially on the basis of signs and symptoms. In the first suspected case, there was no autopsy to confirm CJD, Machala said today. Three more probable CJD deaths were found within 3 weeks after that one.

"That's what prompted us to start an investigation," he said. A review of death records revealed another probable case, for a total of five cases from January through June, he added. All of these were in two counties in south-central Idaho.

Of those five cases, only two triggered full-blown autopsies, which confirmed CJD.

Four other possible CJD cases have occurred: two in eastern Idaho, one in northern Idaho, and one near Boise, Machala said.

An epidemiologist in Idaho is working with a physician from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Machala said. Their research includes a retrospective review of medical records and open-ended questionnaires for families based on World Health Organization (WHO) documents. A preliminary report of their findings should be done in December.

Not all of the cases will turn out to be CJD, and not all of the probable cases can be confirmed, Machala said. Autopsies must be done before embalming, which didn't happen in all the cases. Some pathologists were unwilling to conduct autopsies because they feared exposure to the disease agent, according to an Oct 17 Associated Press (AP) report.

Machala said health professionals have become more aware of signs and symptoms of CJD and are in a better position to draw on resources like the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center at Case Western Reserve University, which works with the CDC and can conduct autopsies appropriate for diagnosis of CJD.

The investigation under way in Idaho, though, won't answer some of the questions people may struggle with the most.

"It's a devastating disease," Machala said. "People are looking for ways to avoid it. That's the trouble: They haven't even figured out what causes it. What triggers it? Is it environmental factors? Is it genetic?"

The lengthy family interviews have included questions about eating habits, occupational exposures, surgeries, travel, and the like, but no smoking gun has emerged.

"One thing is very clear in Idahothe number seems to be higher than the number reported in previous years," Dr. Ermias Belay, a CJD expert at the CDC, told the AP. "So far, the investigations have not found any evidence of any exposure that might be common among the cases."

Both CJD and vCJD are in the group of diseases called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), which can occur in cattle, sheep, buffalo, antelope, and goats, as well as humans.

See also:

Idaho Department of Health and Welfare news release

Idaho Department of Health CJD information

National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center home page

http://www.cjdsurveillance.com/