Two separate studies late last week in Science Immunology document the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in COVID-19 patients at least 3 months after symptom onset.

Both studies suggest that longer-lasting immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies may hold promise as a tool to evaluate viral immune response. One study also demonstrates a correlation between blood and saliva antibody levels, suggesting that saliva could serve as an easier-to-collect alternative to blood testing.

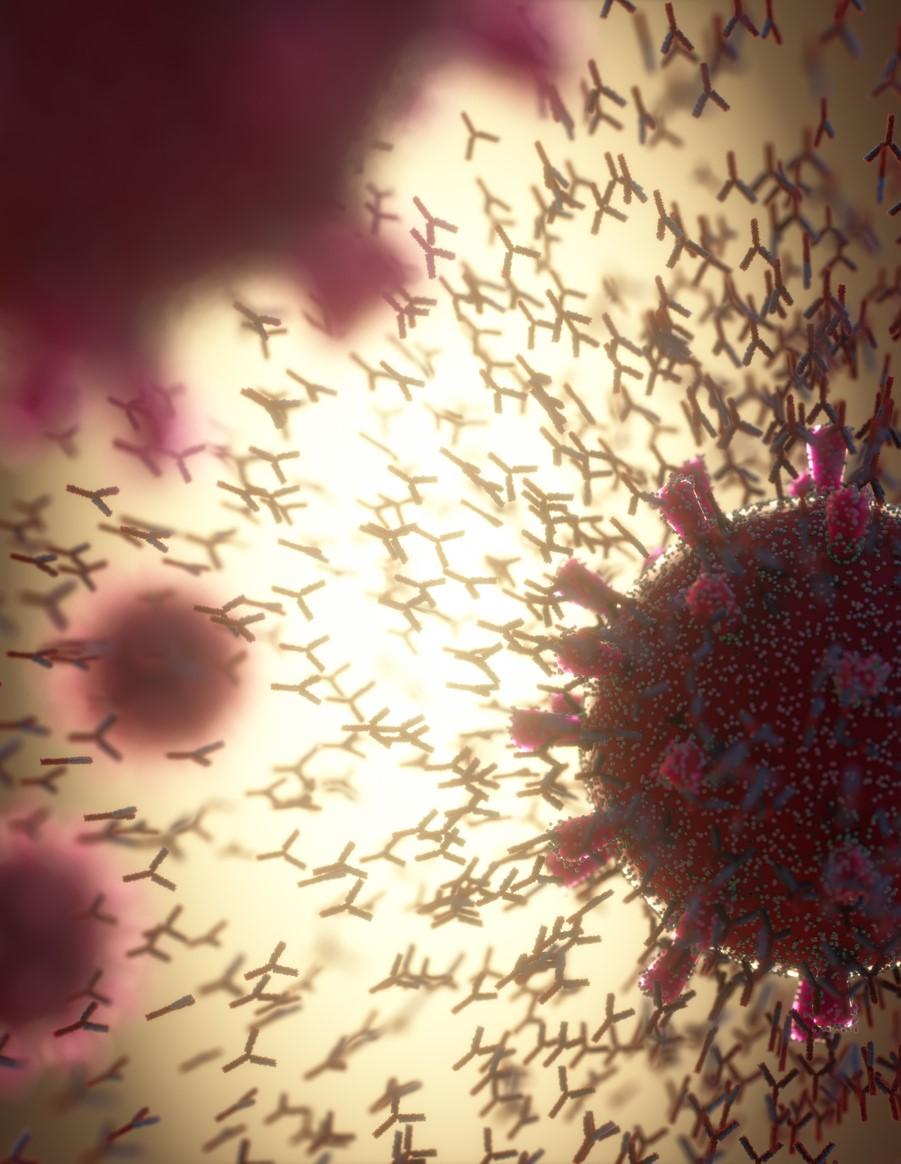

While the presence of COVID-19–specific antibodies—immune molecules generated by the body in response to a virus—has been demonstrated in infected patients, the durability of COVID-19 antibodies is not yet fully understood. Previous studies have shown antibodies diminishing to undetectable levels 2 months after infection in asymptomatic patients.

The duration of antibody response is critical for tracking the spread of COVID-19 as well as to inform vaccine development.

Antibodies elevated for 4 months

In the first new study, researchers measured antibodies specific to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein's receptor binding domain in the blood of 343 patients for up to 122 days after symptom onset, comparing antibody levels to those of 1,548 individuals sampled before the pandemic.

The study authors found that IgG was elevated in patients for 4 months along with protective neutralizing antibodies, with immunoglobulin A and M (IgA and IgM) antibodies relatively short-lived in comparison—both declining to low levels around 2.5 months after symptom onset. Notably, IgG levels were highly effective in identifying patients who had symptoms for at least 14 days, suggesting a role for IgG detection of positive cases missed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, which tends to wane in sensitivity over time.

"Knowing the duration of the immune response by IgA and IgM will help scientists obtain more accurate data about the spread of SARS-CoV-2," explained Jason Harris, MD, in a Massachusetts General Hospital news release. "There are a lot of infections in the community that we do not pick up through PCR testing during acute infection, and this is especially true in areas where access to testing is limited," he said.

Stable antibodies, plus promise for saliva tests

The second study found a similar duration of antibody response among 402 University of Toronto Hospital COVID-19 patients whose antibody responses were recorded from 3 to 115 days after onset. Researchers compared their responses with those from 339 pre-pandemic control patients.

They found that IgA and IgM antibodies rapidly decayed, while IgG antibodies remained relatively stable for up to 105 days after symptom onset.

The authors also found a positive correlation between antibody levels in blood and saliva. "Given that the virus can also be measured in saliva by PCR, using saliva as a biofluid for both virus and antibody measurements may have some diagnostic value," the study authors said in news release from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which publishes the journal.

Implications for persistent immunity

Neither study extended beyond 4 months, limiting the ability to draw conclusions about persistent immunity, but both offer hope that people infected with the virus may develop protection against reinfection.

Acknowledging the knowledge gaps that remain regarding antibody duration and the degree of protection afforded against reinfection, the Toronto study authors point to the potential of durable vaccine antibody response. Jennifer Gommerman, PhD, of the University of Toronto wrote in a university press release, "This study suggests that if a vaccine is properly designed, it has the potential to induce a durable antibody response that can help protect the vaccinated person against the virus that causes COVID-19."

Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, director of the University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, which publishes CIDRAP News, cautions that these studies say nothing about long-term durability. "We need to be careful about interpretation. Three months is not long and tells us virtually nothing about durable immunity 18 to 24 months from now," he said.