An expert committee assembled by the US government to sort out thorny clinical research issues that arose during West Africa's 2013-2016 Ebola outbreak published its report today, weighing in on the trials that took place and recommending steps for streamlining the process in future outbreak settings.

The 16-member group's work was sponsored by the US Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The team held a series of public workshops and committee meetings, did an extensive literature review, and considered written submissions. Findings and recommendations were published in a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Ethics, other clinical trial challenges

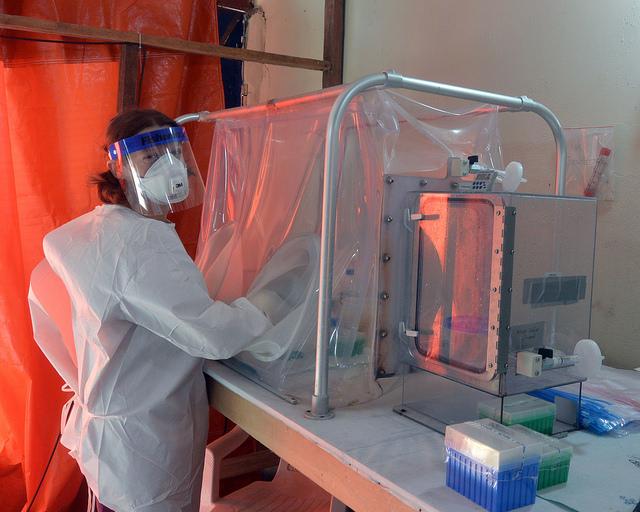

As West Africa's Ebola outbreak spiraled quickly out of control—with no drugs or vaccines to battle the disease—the World Health Organization (WHO) was swamped with proposals for possible treatments, as well as vaccines, and with them, the need for clinical testing.

Generally, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard, and WHO advisors leaned toward that approach, but others objected, because RCTs would involve withholding experimental drugs from members of the control group—especially for such a deadly disease—and draw efforts away from clinical care demands. Another obstacle the science community faced was limited healthcare and research infrastructure in the West African countries affected by the outbreak.

The expert panel's inventory of the clinical trials conducted during the Ebola outbreak found nine: five were therapeutic trials, none of which showed conclusive results, and four were vaccine trials, and only one candidate (VSV-EBOV) had a probable protective effect.

The group concluded that RCTs are ethical and the fastest and most reliable way to weigh the benefits and risks of new products, and except in rare instances, all efforts should be made to implement them during epidemics. They acknowledged that issues about trial design choices, such as community mistrust, the feasibility of a standard-of-care-only arm, and limited product availability, are likely to crop up again in future outbreaks, but the hurdles aren't enough to override the benefits of randomized trials.

Instead, they said RCTs may present the most ethical trial design, because they are the quickest way to identify beneficial treatments while minimizing exposure risks to potentially harmful ones.

Recommendations for future preparedness

To improve the clinical trial response in the next epidemic, the advisors focused on three main areas that can be addressed both before and during the next outbreak: strengthening health system capacity in vulnerable areas, engaging communities, and supporting international coordination and collaboration.

Building research capacity cannot and should not be separated from building health systems in general, and clinical research needs to be embedded within healthcare systems, especially regarding the collection and sharing of data, the team urged. Though the need to improve fragile healthcare systems was one of the main lessons learned during the Ebola outbreak, it's not clear if limited international donor support has had an impact.

As responders learned during the outbreak, community members had fear, mistrust, and misunderstanding of public health steps and research efforts. The group said successful clinical research depends on a community's understanding and engagement in the study planning and roll-out.

Regarding research collaboration, the group found that one of the obstacles was limited ways of prioritizing what to study first.

One of their recommendations is an international stakeholder coalition to work between epidemics to advise and prioritize the pathogens to target for future research, develop clinical trial templates, and earmark research teams that could be deployed to help during outbreaks.

They considered three models: the WHO, the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) , and the newly launched Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations (CEPI). CEPI is an international partnership that launched in January with the goal of streamlining and advancing the pipeline for public health threats. Armed with $460 million, it announced that its initial focus is developing vaccines against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), Lassa, and Nipah virus.

The National Academies report said CEPI, though it is new and focused on vaccines, has the "right DNA for the job" and has the potential to coordinate and cooperate on the development of new safe and effective therapies. Drawbacks of depending on the WHO to coordinate and prioritize research in epidemics include its limited staffing, big demands, and dependence on donor funds. The GHSA model, launched by the United States with 55 partners in 2014 to facilitate the global battle against disease threats, has a complex agenda that isn't focused on research and development.

"Furthermore, GHSA is driven by one country, and its priorities and commitments may change with changes in national leadership," the group wrote in its report. So far, it's not clear where the Trump Administration goals are with global health issues, but one of the themes of the presidential campaign was a more inward-looking "America first" approach.

See also:

Apr 12 National Academies press release

Apr 12 National Academies report highlights

Apr 12 National Academies report