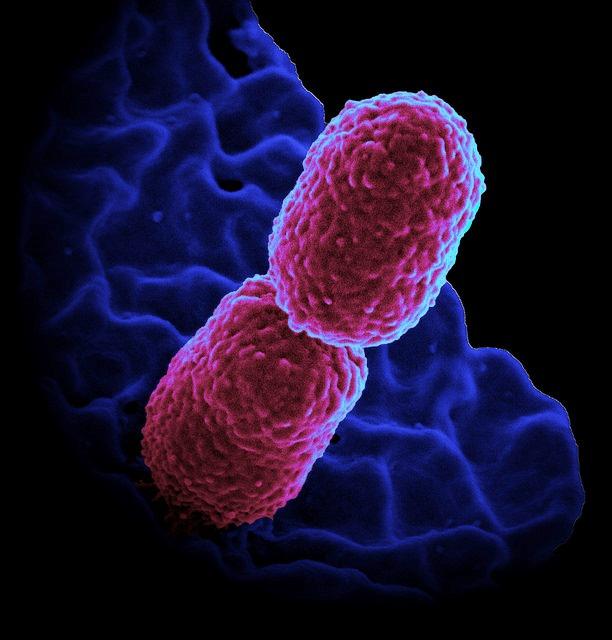

Infectious disease experts are calling the emergence of hypervirulent, multidrug-resistant and highly transmissible strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae described in a recent paper by Chinese scientists an alarming and worrisome development that could be a sign of things to come.

The paper, published last week in the Lancet Infectious Diseases, described a ventilator-associated pneumonia outbreak among five patients in an intensive care unit (ICU) at a hospital in Hangzhou, China. The five patients, who had suffered severe trauma from car accidents and other incidents, developed pneumonia after undergoing multiple surgeries, did not respond to any antibiotic treatment, and died over the course of several weeks from severe lung infection, multi-organ failure, or septic shock.

Further investigation of the cases revealed the pneumonia had been caused by strains of K pneumoniae bacteria that are a common cause of infection in Asia, but unlike any the investigators had previously seen in healthcare settings, harboring both antibiotic resistance genes and hypervirulence genes—a combination of K pneumoniae that causes severe, quick-developing, and deadly infections and is nearly impossible to treat with currently available drugs.

The authors of the paper called these new strains, which they also found in a small percentage of K pneumoniae samples from other Chinese hospitals, a "real superbug" that is an imminent threat to public health. The authors of an accompanying commentary called the findings "an alarming evolutionary event." And experts who've spoken with CIDRAP News about the study share these concerns.

"The fatal outbreak of a hypervirulent and hyper-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese ICU represents a worst-case scenario in which both resistance elements and virulence factors appeared in the same strain of bacteria," Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior associate at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, said. "The situation highlights the dire threat of antibiotic resistance and is a harbinger of the future if current trends continue."

More severe than typical pneumonia infections

Ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by drug-resistant bacteria is fairly common in healthcare facilities, especially among patients with severely compromised immune systems. And such infections can frequently be deadly, with mortality rates as high as 50%. But Sheng Chen, PhD, lead author of the study and a microbiologist at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, said that the pneumonia in these five patients was different.

"We felt that the pneumonia in these patients was more severe than typical pneumonia infections," he said.

Chen and his colleagues identified the K pneumoniae bacteria that were the underlying cause of the infections as belonging to sequence type (ST) 11, a lineage that's responsible for 60% of K pneumoniae infections in Asia and is known to harbor genes that confer resistance to carbapenems and other beta-lactam antibiotics. And they all appear to have emerged and spread from a single clone found in an index patient, who was admitted to the ICU in February 2016.

Molecular analysis of the K pneumoniae samples from the five patients showed that they contained several antibiotic resistance genes, and laboratory tests confirmed what doctors had reported—that the bacteria were also extremely virulent, a trait not typically associated with ST11 strains.

That's because, as further genomic analysis revealed, the bacteria were carrying virulence genes associated with hypervirulent strains of K pneumoniae, which have emerged globally in recent years but are less common than ST11 and other K pneumoniae strains that cause healthcare-associated infections (often referred to as "classical" K pneumoniae strains). The genes were found on plasmids, which are small, highly mobile pieces of DNA that can be shared among bacteria.

"In this case it looks like the virulence factors went from the hypervirulent strains into an extensively drug-resistant strain," said Thomas Russo, MD, an infectious disease expert at the University of Buffalo's Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. "This is exactly what we were concerned about, and we thought would have a high likelihood of coming to fruition."

A 'harrowing' combination

Russo, whose research focuses on gram-negative bacteria, has become familiar with hypervirulent K pneumoniae strains in recent years, co-authoring several studies. What's different and scary about the hypervirulent strains of the bacterium, he explained, is that they tend to cause disease in the community, among otherwise healthy people. In addition, they can spread very quickly to anywhere in the body from the initial site of infection, which is "extraordinarily unusual" for gram-negative bacteria like Klebsiella, he said.

Russo has been concerned about the potential merging of these two types of K pneumoniae because of horizontal gene transfer—the process through which bacteria acquire plasmid-mediated resistance and virulence genes. The question he has is whether the ST11 K pneumoniae strains described in the Chinese study have acquired all the genes on the virulence plasmid and become fully hypervirulent.

In addition, he worries about fully hypervirulent strains acquiring resistance mutations, a development that could give rise to extremely drug-resistant K pneumoniae infections in relatively healthy people.

"You can imagine the genetic material could go in either direction, with the hypervirulent strains acquiring plasmids that contain the resistance genes," he said.

To date, hypervirulent K pneumoniae strains have not appeared to be resistant to antibiotics. And in general, Adalja added, most infectious disease experts believe that highly antibiotic resistant bacteria tend to be less virulent because there is usually a fitness cost associated with resistance mutations. That's one of the noteworthy developments highlighted by the Lancet paper.

"The Chinese cases highlight that this is not necessarily the case and this combination of traits can exist, and when it does, it is harrowing," Adalja said.

Prevalence low, but spread likely

To get a better sense of whether the K pneumoniae strains that infected the patients were in other hospitals, Chen and his colleagues noted in their Lancet paper that they conducted a retrospective analysis of 387 clinical ST11, carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae isolates from hospitals in 25 Chinese provinces and municipalities. They found that only 11 (3%) also carried the virulence plasmid. Five of those patients died, and six were discharged with critical illnesses.

While the overall prevalence of hypervirulent, drug-resistant K pneumoniae in China appears to be low, Chen said, what he and his colleagues are worried about is that it will likely increase in Chinese hospitals, presenting clinicians with more severe infections that don't respond to the current arsenal of antibiotics.

But with few new antibiotics in the pipeline, physicians will be forced to keep using what they have, which will only hasten the further emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens, said David van Duin, MD, PhD, an antimicrobial resistance researcher at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. "Emergence of combined increased virulence and resistance will force doctors to treat patients even more broadly upfront with last-line antibiotics, thus inducing additional resistance," he said.

And if the rapid global spread of the resistance gene MCR-1 is any example, these types of infections won't be limited to China. The plasmid-mediated gene, which confers resistance to the last-resort antibiotic colistin, was identified in Escherichia coli bacteria in China in 2015, and since then has been detected in more than 30 countries. Other antibiotic resistance genes have demonstrated similar ability to spread rapidly via horizontal gene transfer. The genes and plasmids, and the bacteria that carry them, know no boundaries.

"Multidrug-resistant organisms in one part of the world are a threat to patients everywhere," van Duin said.

See also:

Aug 29 Lancet Infect Dis study

Aug 29 Lancet Infect Dis commentary

Aug 30 CIDRAP News story "Hypervirulent, highly resistant Klebsiella identified in China"