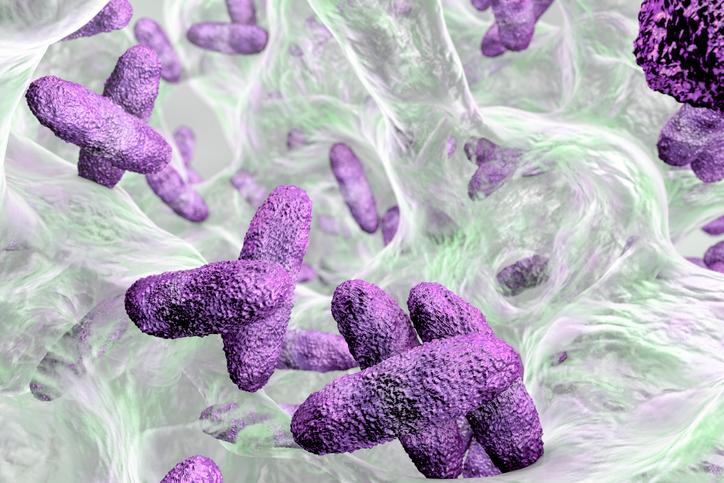

Researchers in China are now suggesting that strains of hypervirulent, multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae that caused a deadly pneumonia outbreak at a Chinese hospital last year emerged earlier and are more widespread than initially reported.

In three letters published yesterday in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, the researchers report that the hypervirulent strains of ST11 carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae (CRKP) described in a paper in August likely emerged before 2015, and that other strains of hypervirulent, antibiotic-resistant K pneumoniae are present in the Chinese healthcare system (including Hong Kong) and may be even harder to treat.

They say the prevalence of the highly transmissible strains in China and throughout the world should be assessed in order to create adequate infection control policies.

Earlier report detailed Chinese cluster

The original paper, also published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, described a ventilator-associated pneumonia outbreak among five patients in an intensive care unit at a hospital in Hangzhou, China, in 2016.

The patients, who had suffered severe trauma from car accidents and other incidents, developed pneumonia after undergoing multiple surgeries, did not respond to any antibiotic treatment, and died over the course of several weeks from severe lung infection, multi-organ failure, or septic shock. Further investigation revealed that the pneumonia had been caused by strains of K pneumoniae that belonged to the ST11 lineage.

ST11 K pneumoniae strains are a common cause of healthcare-associated infections in China, and strains carrying antibiotic resistance genes are a growing concern. But these strains were different, harboring both antibiotic resistance genes and hypervirulence genes on plasmids, which are small, highly mobile pieces of DNA that can be shared among bacteria. The strains are capable of causing severe, quick-developing, and multidrug-resistant infections both in hospitals and the community. A retrospective analysis of 387 ST11 CRKP isolates from hospitals in 25 Chinese provinces found that 11 (3%) also carried the hypervirulence genes.

The authors of the study called the strains "a real superbug that could pose a serious threat to public health."

Strains emerged in 2013

In one of the letters, researchers with Beijing Key Laboratory of Emerging Infectious Diseases describe screening the whole genome of 141 K pneumoniae strains from 42 hospitals in 19 provinces dating back to 2009 and 2013-14. The retrospective screening identified three hypervirulent ST11 CRKP strains that emerged in 2013 and one 2014.

They also identified hypervirulence genes in other strains of antibiotic resistant K pneumoniae and found that hypervirulent strains carrying a plasmid similar to that described in the earlier study are more likely to be drug-resistant.

"Our 2009 and 2013-14 surveillance data…indicated that the dissemination of the antimicrobial-resistant hvKP [hypervirulent K pneumoniae] strain should be urgently prevented in China, and the identification of an effective clinical treatment is paramount," they write.

In another letter, researchers in human and animal health screened 253 K pneumoniae strains from clinical patients and 102 strains obtained from pigs from 2011 through 2016 for the presence of carbapenemase and hypervirulence genes. The analysis revealed four hypervirulent ST11 CRKP strains among the patient samples, one of which also contained a gene conferring resistance to tigecycline. This finding, the authors write, "further restricts the treatment options for this notorious pathogen."

In the third research letter, scientists in Hong Kong found that 7 of 65 K pneumoniae bloodstream isolates collected at a Hong Kong hospital from 2016 to 2017 harbored several different carbapenem-resistance genes, and 3 of those isolates also carried hypervirulence genes.

While the overall prevalence of clinical CRKP strains in Hong Kong remains low, the authors suggest the high transmissibility of hypervirulent CRKP strains could pose a threat to Hong Kong's healthcare system in the future. They say more epidemiologic studies are needed to assess the threat.

Persistent CRKP infections

In a related letter, researchers at the same hospital where the initial CRKP patients were identified describe the case of a 69-year-old man who had been admitted to the hospital 4 years earlier, in 2012. The patient had a sequential CRKP infection that lasted for 5 years, despite treatment with more than 13 different antibiotics. He ultimately died in March 2017 of septic shock and multiple organ failure.

Analysis of the seven identified strains of CRKP in the patient did not detect any the hypervirulence genes. But further tests revealed that CRKP can survive within lung epithelial cells, protected from immune cells and antibiotics by the cell membrane.

"Survival of CRKP within cells might serve as a reservoir—protected from antibiotic treatments—that enables long-term coexistence with the host, which might explain the recurrence of infections and relapses after antibiotic therapy," the authors write.

See also:

Nov 1 Lancet Infect Dis first letter

Nov 1 Lancet Infect Dis second letter

Nov 1 Lancet Infect Dis third letter

Nov 1 Lancet Infect Dis fourth letter

Aug 30 CIDRAP News story "Hypervirulent, highly resistant Klebsiella identified in China"

Sep 8 CIDRAP News story "New Klebsiella strains 'worst-case' scenario, experts say"