The shorter and milder winters, warming oceans, altered precipitation patterns, and extreme weather of climate change are fueling the spread of infectious diseases, experts warn today in JAMA.

Infectious-disease physicians from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the University of California Davis (UCD) noted that the past decade saw 9 of the 10 warmest years on record, along with severe heat, droughts, wildfires, floods, and hurricanes.

"Primarily due to greenhouse gases released via combustion of fossil fuels, global average temperatures between 2011 and 2020 increased to 1.1°C (approximately 1.9°F) above preindustrial levels and are estimated to increase to 1.5°C (approximately 2.7°F) by 2040," they wrote.

These changes are in turn spurring alterations in pathogens and parasites and in the behavior of animals and people around the world. "Awareness of changes in the geographic range, seasonality, and frequency of transmission of infectious diseases because of climate change is important to help clinicians diagnose, treat, and prevent infectious diseases in patients," the authors wrote.

Atypical ranges, seasons, hosts

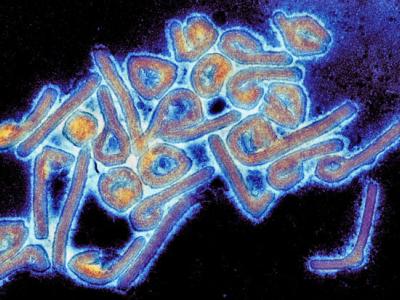

Changes in vector-borne, zoonotic, fungal, and waterborne diseases are already occurring. For example, from 2004 to 2018, the number of cases of arthropod-related disease in the United States more than doubled, to more than 760,000, the authors said, citing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These include tick- and mosquito-borne illnesses such as those caused by the Zika, Powassan, and West Nile viruses.

"This increase may be related to improved awareness, diagnostic methods, and case reporting, but climate-related changes in vector biology are also contributing," the physicians wrote. "For instance, tick survival over winter months increases with shorter, milder winters, leading to larger populations and northern extension of their geographic locations into Canada and the upper Midwest US."

Migratory birds are uniquely affected by habitat destruction and have been the primary cause of the current global outbreak of avian influenza (H5N1).

In a UCD news release, lead author Matthew Phillips, MD, PhD, of MGH, said malaria is of increasing concern. "As an infectious disease clinician, one of the scariest things that happened last summer was the locally acquired cases of malaria," he said. "We saw cases in Texas and Florida and then all the way north in Maryland, which was really surprising."

The team noted models that estimate that more than half of the world's animal species are seeing climate-related changes in their natural ranges, with many heading toward cooler temperatures in the north.

"Habitat destruction leads to numerous species coming into close contact, increasing the risk of pathogens (particularly viruses) spreading to other species, potentially including humans," they wrote. "Migratory birds are uniquely affected by habitat destruction and have been the primary cause of the current global outbreak of avian influenza (H5N1)."

Physicians need to stay vigilant

The authors said that while most fungi can't grow in people because they can't tolerate humans' body temperatures, fungi may become tolerant to warming ambient temperatures. Sporothrix brasiliensis, for example, seems to have switched from being a plant-dwelling organism to a cause of disease in people and cats through its ability to grow at warmer temperatures in parts of South America.

Other waterborne pathogens, such as Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, and Cryptosporidium, cause diarrheal disease after flooding and are worsening with extreme weather events and warmer climates.

As sea levels rise, extreme storm surges and coastal floods are predicted to take place 20 to 30 times more often by 2050. "These events, combined with warming, increase contact with coastal pathogens (eg, Vibrio species), which can cause gastroenteritis, soft tissue infections, and sepsis, with mortality rates of up to 50%," the experts wrote. "Other waterborne pathogens, such as Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, and Cryptosporidium, cause diarrheal disease after flooding and are worsening with extreme weather events and warmer climates."

Healthcare providers should be vigilant for infectious diseases with changing ranges and hosts. "Clinicians need to be ready to deal with the changes in the infectious disease landscape," senior author George Thompson III, MD, of UCD, said in the release. "Learning about the connection between climate change and disease behavior can help guide diagnoses, treatment and prevention of infectious diseases."

Similarly, physicians should stay involved in related policy issues, because infectious diseases "can spring up and cause absolute chaos for the whole world, and then we kind of forget about them for a while," Thompson said. "Yet, the epidemic and pandemic potential of infections really mandates that we stay involved with federal funding agencies and advisory groups to make sure that infectious diseases don't slip back too far on the public's radar."