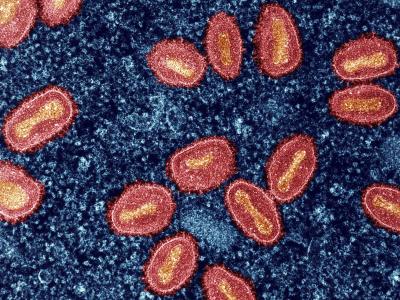

Jan 14, 2004 (CIDRAP News) The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said this week that the case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in the United States signals that many countries need to strengthen their BSE-control programs.

The organization recommended six specific preventive steps for all countries. The FAO also endorsed testing of all older cattle for BSE in countries where the disease is presentan expensive step that US officials have made no move to take.

"In many countries, BSE controls are still not sufficient and many countries are not applying the recommended measures properly," the FAO stated. "There is also a considerable risk of further introducing infectious materials, given the global trade in animal feed and animal products."

The agency urged countries to assess their risk of BSE and to guard against it by strictly applying the following measures:

- Banning the feeding of meat-and-bone meal to farm animals, or at least to ruminants (cud-chewing animals such as cattle and sheep)

- Preventing cross-contamination in feed mills to keep cattle parts intended for poultry or hog feed from ending up in cattle feed

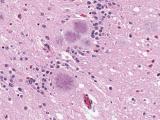

- Removing and destroying "specified risk materials" (SRMstissues such as the brain, spinal cord, and certain nerve bundles, which are most likely to carry the BSE agent in infected animals) from carcasses of cattle over 30 months old

- Ensuring safe practices in the rendering industry, ie, exposing material to 133˚C at 3 bar pressure for 20 minutes

- Using active surveillance for BSE and providing for accurate identification and tracing of animals throughout production, processing, and marketing

- Banning the use of mechanically removed meat

"With these control measures in place, especially with the feed ban and removal of SRMs, the risk of BSE infective material being present in the food chain is extremely low," the FAO said.

One safeguard not on the list is a ban on using downer cattlethose that can't walk when presented for slaughterfor human food. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced such a ban Dec 30, a week after the first US case of BSE was identified in a downer cow.

The United States banned the feeding of cattle meat-and-bone meal to ruminants in 1997, but it can still be fed to poultry and hogs. In response to the BSE case, the USDA recently began requiring the removal of specified risk materials from carcasses, promised to speed the development of an identification system for all cattle, and banned the use of mechanically separated meat in human food. (The agency defines mechanically separated meat as meat produced with machines that crush and grind bones. Meat from "advanced meat recovery" (AMR) systems, which separate meat without breaking bones, can still be used as food, but it cannot contain spinal cord tissue or nerve bundles.)

Broad testing recommended

Concerning the testing of cattle for BSE, the FAO cited the OIE (World Organization for Animal Health) recommendation that countries test 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 10,000 cattle over 30 months old, as well as cattle with possible BSE symptoms. The USDA tested about 20,000 cattle last year, more than necessary under the OIE recommendation, the FAO said.

But the agency added, "If BSE is known to be present and control measures have not yet been strictly applied, a wider testing program is called for. . . . Testing of all slaughter cattle over 30 months is a measure to enhance consumer confidence."

The FAO said the European Union tested more than 9 million cattle in 2002 and 2003, and Japan tested almost every cow.

Testing all older cattle would mean a huge increase in testing in the United States. USDA officials have said the US beef industry processes about 35 million cattle annually, of which about 20%, or 7 million, are older than 30 months. Before the BSE case discovery, the USDA had indicated plans to test about 40,000 cattle for BSE this year.

The FAO estimated the cost of BSE testing at about $50 per animal. "Considering the potential damage of BSE outbreaks to human health and meat markets, testing can be considered cost-effective," the agency said.

Randall Levings, director of the USDA's national veterinary laboratory in Ames, Iowa, recently said BSE tests cost the USDA about $100 apiece, according to a Jan 12 report in the Omaha World-Herald. He said the lab could possibly increase its BSE testing rate to several hundred thousand samples a year, but not millions.

Another at-risk cow traced

In related news, the USDA said today it has found another cow that was imported into the United States from Canada with the BSE-infected cow in Washington state. The cow is at a dairy farm in Quincy, Wash. The herd there may include up to six other cows from the infected cow's birth herd in Canada. USDA is tracing animals from the birth herd because they may have eaten the same feed as the infected cow, which could put them at risk for BSE.

Three other cattle from the birth herd were previously found in Mattawa, Wash., and will be removed soon, the USDA said. Nine other cows from the Canadian herd are at the Mabton, Wash., farm where the infected cow lived out its last days. USDA said it is continuing the process, begun Jan 10, of removing and euthanizing about 130 animals from the Mabton herd.

See also:

FAO news release

http://www.fao.org/english/newsroom/news/2003/26999-en.html

USDA's Jan 14 update

http://www.usda.gov/Newsroom/0016.04.html