Mar 17, 2008 (CIDRAP News) – In the early stages of an influenza pandemic, cases are spreading among migrant workers in Michigan. The state's health department has a supply of antiviral drugs from the federal stockpile and is using them to treat the sick, but, concerned about breaking federal rules, is withholding them from others exposed to the virus—thereby missing a chance to help contain it.

Meanwhile, cases are spreading among homeless people in Washington, DC, and authorities are getting ready to close the schools, but they want to know what to do about children who depend on the school lunch program and those whose parents can't take time off work to care for them.

Those were two of the many dilemmas raised in a major pandemic simulation exercise staged at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta last week. Others included how to keep travelers from spreading the virus and what to do in the face of serious side effects caused by the leading antiviral drug.

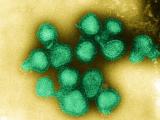

It was the fourth in a series of exercises based on a scenario that puts the United States at the epicenter of an evolving pandemic featuring an H5N1 strain of flu. Instead of watching anxiously as a pandemic emerges on some other continent, the scenario goes, the United States has about 75% of the world's cases, all stemming from a traveler from Southeast Asia who brought the virus into the country. The series of exercises began in January 2007.

Although the event was only an exercise, it offered a close-up look at the CDC's expectations about the kinds of challenges it will face in the early stages of a real pandemic and how it might be likely to respond.

The simulation involved a total of roughly 1,000 people, most of them from the CDC but also a number from other government agencies, according to Von Roebuck, a CDC spokesman who hosted reporters witnessing the drill.

CDC emergency center buzzing

The 2-day event took place in the Director's Emergency Operations Center (DEOC) on the third floor of the gleaming CDC headquarters building on the Atlanta campus. There, specialists from many CDC branches and a few other agencies staffed computer stations laid out in long rows, with 60 stations in all, most of them occupied. They faced a wall filled with a dozen or more electronic displays that charted data on influenza cases and deaths, distribution of antivirals, deployment of CDC personnel, CDC goals and objectives, and various other dimensions of the pandemic and response. Flanking the data displays were two TV news feeds.

A similar but smaller control room a couple of buildings away was occupied by the CDC's Exercise Control Group, consisting of 51 people who designed and monitored the exercise, adding new wrinkles that the CDC had to respond to as it evolved. Some played roles as representatives of other federal agencies or state health departments.

As played out in the first exercise last year, the pandemic scenario began with an apparently healthy but infectious man from Southeast Asia who traveled to the United States, exposing other travelers on the way. After falling ill, he exposed household contacts, healthcare workers, and some members of a university sports team.

Soon, as depicted in subsequent exercises, cases linked to the index patient surfaced in 10 states, plus Washington, DC, the Marshall Islands, Guam, and several foreign countries, including Australia, India, the United Kingdom, Panama, Japan, and Canada. Early on, the CDC determined that the prepandemic H5N1 vaccine in the US stockpile was not of much use against the pandemic strain. But the agency began shipping antivirals, mainly oseltamivir (Tamiflu), to the states, allocating them in proportion to population.

By the time last week's exercise opened on Tuesday, which was termed the sixth day of the CDC's emergency response, there were 273 US cases and 27 deaths. The exercise began with a meeting involving CDC Director Dr. Julie Gerberding and about 25 senior staff members in a glass-walled conference room adjoining the DEOC. Sound from the meeting was piped—not always very audibly—into the main room.

As the exercise unfolded over the 2 days, cases mounted, slowly here, in spurts there. CDC officials hashed out responses in the early morning briefings and in conference calls with state officials; they announced decisions and recommendations at mock press briefings each morning and afternoon.

School closing confusion

The question of school closings and related "community mitigation" (CM) measures (also known as nonpharmaceutical interventions, or NPIs) arose early and often. At the first morning press briefing, Gerberding said, "As of this morning we're not recommending widespread school closures or other measures to reduce spread in crowds, but those measures are likely." She added that actual closings would be local decisions.

When she was asked what should trigger CM measures, Gerberding said, "When a community begins to see acceleration in the number of cases that suggests that transmission is really taking off, that's when closing schools and avoiding crowds can help. It's important to do it early, because if you wait till you have 1,000 or 10,000 cases, it's too late."

Hesitation and concerns about CM measures emerged in an hour-long Tuesday afternoon teleconference between senior CDC staffers and health officials from states affected by the pandemic. (The state officials were mostly played by CDC staffers in the Exercise Control Group, but three people from state health departments had joined the group for the exercise, according to Jerry Jones, director of the group.)

The Michigan official wanted to know if the CDC could recommend any particular NPIs as better than others. He said the state had a case-fatality rate of 7% in its 100 cases, signaling a severe pandemic under the CDC's community mitigation plan, so the state needed to launch mitigation steps. "But the local health departments are telling us they don't want to do all that work," he said. "So if there's one thing working better than others, we'd like to recommend it."

The answer from the CDC team was negative. "We need to really discourage people from picking and choosing different things. They need to be implemented simultaneously," said one official. However, the officials said mitigation steps could be limited to specific communities rather than covering the whole state.

Another official cited last year's report in the Journal of the American Medical Association on the effectiveness of NPIs in the 1918 pandemic, including school closures, banning public gatherings, isolation of patients, and quarantine of contacts. "If you need ammunition, that's what to use," he said.

A few minutes later, a Washington, DC, official raised concerns. "We get a lot of pushback about the need to wait to work on these school closures," she said. The three main issues, she said, had to do with children dependent on the school lunch program, children whose parents can't take time off work, and what to do about teachers' salaries.

The CDC officials deferred to others on that issue, saying the Department of Education was supposed to be developing relevant guidance. "These problems require resources that we don't have authority over," said Dr. Stephen Redd, the CDC's influenza team leader.

School closures came up again on Wednesday, the second day of the exercise.

In response to questions at the morning press conference, Redd said, "There will not be a federal decision on school closings. This needs to be a local decision." He added that schools were already closed in affected areas of Michigan and Arkansas.

But in another conference with state health officials that afternoon, uncertainty was still evident. Ohio, which was reporting 18 cases, was getting a lot of questions and concern about whether schools would close, especially in Toledo, a state official reported. He expressed concern that parents would start keeping their children home and said he wasn't sure what the state's trigger for closing schools was.

CDC officials responded by repeating the criteria for launching NPIs and said a document explaining them would be posted on the government's pandemic flu Web site later in the day.

Debating guidance on antivirals

With no effective vaccine available, health authorities were forced to rely on antiviral drugs to fight the virus, under the scenario. Earlier chapters in the exercise brought the news that the prepandemic H5N1 vaccine in the US stockpile was too poor a match for the pandemic virus to be of much use. The CDC decided to distribute antivirals from the national stockpile to all the states in proportion to population. Roebuck, the CDC spokesman, said the real stockpile currently contains 39.8 million treatment courses of oseltamivir and 9.9 million courses of zanamivir (Relenza).

The drugs were being shipped to the state health departments in stages, with each state first receiving 25% of its share and then getting another 50% later. The CDC planned to hold the last 25% in reserve. At the Wednesday news briefing, Redd said about 30% of the stockpile had been delivered so far, and the expectation was that the 75% mark would be reached within the ensuing week. In a real pandemic, state health departments will be responsible for distributing the antivirals to healthcare providers according to their preexisting plans, said Dr. Richard Besser, director of the CDC's Coordinating Office for Terrorism Preparedness and Emergency Response.

Because of the limited supply, the CDC's recommendation was to use the antivirals to treat sick people, not to prevent flu in their contacts, although small amounts could be used for "initial containment in some locations," Gerberding said at the Tuesday morning news conference. "The deployment is to make sure that hospitals have drugs available when people are sick," she said.

Whether to use antivirals for prophylaxis sparked a lively discussion at the Wednesday teleconference of CDC leaders and state health officials. A Michigan official said the state was calling for community mitigation measures in affected migrant worker camps and neighboring towns, but some of the neighboring towns were reluctant to take those steps. As a result, he said, state officials were worried that the virus would move from the camps to the nearby communities and start spreading. In response, a CDC official recommended that the state use antivirals for prevention in those areas.

"We've been using them only for treatment so far," the Michigan official replied. "We would be happy to use them for prophylaxis at this time, but we need more clarification from the SNS [Strategic National Stockpile]" on policy.

Another CDC official observed that the official guidance was that the antivirals should be used only for treatment. But in further discussion the CDC conferees agreed it would be appropriate for Michigan to use the antivirals for prophylaxis under the circumstances.

"I'll make a decision," one CDC official volunteered. "Go ahead and give them some."

"Can I get that in writing?" the Michigan official asked. He was assured that he would, and the CDC officials concluded it was time to issue specific guidance to the states on how and when to use their antivirals.

A few minutes later, two other states reported no hesitation in using antivirals preventively. An Ohio official reported "a lot of success" in treating both the sick and their healthy contacts with the drugs. And an Arkansas health official told the CDC people that state authorities had decided several days earlier to give preventive antiviral treatment to everyone in the town of Pea Ridge, where the state's cases were concentrated.

But the prophylactic use of antivirals had a serious downside in the exercise scenario. At the Wednesday morning press conference, Dr. Carolyn Bridges of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases reported that two Arkansas teenagers had committed suicide after receiving oseltamivir.

She noted that a label warning about possible neuropsychiatric side effects of oseltamivir had been added after reports of such events in young patients in Japan, though there has been very little information to directly link the drug with such reactions.

Calling the suicides "tragic," Bridges urged healthcare providers to report any adverse events through the MedWatch system. But in the face of a rapidly spreading virus that causes severe illness, the CDC was not changing its recommendations on the use of oseltamivir, she said.

A plan to screen travelers

Another containment strategy invoked in the exercise, though in a limited way, was to screen incoming travelers in areas not yet affected by the pandemic. At the Tuesday afternoon press conference, Dr. Francisco Averhoff of the CDC Division of Global Migration and Quarantine announced a screening program designed to slow the spread of flu into Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, which were not yet reporting cases.

The plan, he said, was to funnel all airline flights to one airport for each of those jurisdictions—Anchorage, Honolulu, and San Juan—and to screen all arriving passengers with a visual check, health questionnaire, and physical exam. Sick passengers were to be isolated and treated, and their contacts quarantined.

This plan had aroused considerable concern in state officials when it was described at the CDC conference call with state officials earlier the same afternoon. The Department of Homeland Security was to conduct the primary visual check of incoming passengers, and the CDC was to do the medical screening, with an interview and physical exam. Each state health department was asked to provide 20 staffers to help out with evaluating passengers, isolating and treating patients, and quarantining contacts, CDC officials said.

"You're asking us to give up 20 of our staff?" replied a Dr. James from Alaska. "That's just not realistic for us to give up that many. That's practically our whole staff." Similarly, a Hawaiian official added that it would "extremely difficult" for his state to provide the help the CDC was requesting.

The state officials said they would try to assign staff members to help with the effort, but they needed information on what kinds of workers the CDC wanted. CDC officials promised to send a list.

At the news conference, a "reporter" asked how much good the screening program could do, given that the virus had a 2-day incubation period and apparently healthy travelers could be infected.

"The screening isn't foolproof," acknowledged Dr. Stephen Redd, the influenza team leader. "What we're trying to do is decrease the numbers and the burden of disease in a community. We know it's not going to completely keep the virus out of these areas. We know that complete closure of the borders does not work. You would only slow the introduction."

When he was asked about screening at land border stations, Redd said the government had no major plans for enhanced screening. "We're working in collaboration with Canada and Mexico. We feel that activities at land ports of entry would not be effective. It would be a misuse of our resources," he said.

Similarly, at the Tuesday morning news conference Gerberding reported there were no plans for increased screening of incoming international travelers other than places like Alaska and Puerto Rico. "The fact is we have the most cases of anywhere in the world. It's not likely that doing things to keep people out will make much difference," she said.

However, the CDC was taking action when incoming international travelers with suspicious symptoms were identified during normal screening. At the Wednesday afternoon teleconference with state health officials, Averhoff said 300 airline passengers from Europe had been quarantined on arrival in Georgia after three people on the flight were found to be ill with possible pandemic flu.

At the Wednesday morning news conference, Redd was asked about screening of travelers leaving the United States. He replied that the CDC was consulting with the WHO about exit screening at airports, adding, "We think the measures we're using in the U.S. would be more effective than exit screening, so we hope not to go that way." He explained that self-isolation of patients and voluntary quarantine of contacts seemed to be paying off in Michigan and Arkansas.

Other observations

The exercise covered many other issues and concerns. Here are a few:

- The 10% case-fatality rate in the scenario was worse than in the 1918 pandemic and "out of bounds of our planning scenarios," said Gerberding.

- While noting the high fatality rate, Redd said, "Really the question is how widespread is this going to become?" Would it spread fairly slowly, like SARS, or would it travel much faster, like seasonal flu? "There's kind of a sense that in some areas the local control measures are being effective," he said.

- In the scenario, the pandemic virus was spreading while seasonal flu was still active. However, not much was said about how clinicians might distinguish the two illnesses, aside from laboratory testing. One official said current tests can identify an H5N1 virus in 3 to 4 hours after a sample reaches the lab.

- In one of the staff conferences, Gerberding called for creation of a video on how to use a simple face (surgical) mask, recommended for flu patients to protect others from their respiratory droplets. She also said the CDC should advise the public what could be used as a substitute if masks run short. "We need to lean forward with the expectation that we're going to run out of masks," she said.

- At one of the news conferences, Redd advised the public to stockpile enough food and water to last 2 weeks. The scenario did not include any major economic repercussions such as shortages of food, fuel, medicine, or other commodities.