Legionnaires' disease cases have quadrupled since 2000, marked by recent high-profile outbreaks in New York City, Illinois, and Michigan, but most are preventable with simple steps by building owners and managers, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said today in a Vital Signs report.

At a media briefing, CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, said the reason for the steep rise is probably a combination of factors that include aging building water systems, an aging population that is more susceptible to the disease, and better diagnostic tools and reporting.

In today's report, CDC researchers analyzed 27 building-linked Legionnaires' disease outbreaks that the agency investigated from 2000 to 2014 and identified four key flaws that played a role in many of the events. Alongside the findings, the CDC released a new toolkit for building owners and managers.

"Many of the Legionnaires' disease outbreaks in the United States over the past 15 years could have been prevented," Frieden said in a statement. "Better water system management is the best way to reduce illness and save lives, and today's report promotes tools to make that happen."

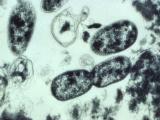

July will mark the 40-year anniversary of the Legionnaires' disease outbreak at a Philadelphia hotel, Frieden said, adding the disease has a special place in CDC history because of the size of the outbreak and the involvement of CDC investigators. It is caused by infection with Legionella bacteria.

High-profile outbreaks, vulnerable populations

Legionellosis can cause flu-like symptom such as fever, chills, and cough. Older people and those with compromised immune systems are most vulnerable, and the infections are fatal in 10% of cases.

In 2015, about 5,000 Legionnaires' disease cases were reported, and the CDC received reports of more than 20 outbreaks. Some that made headlines include one in the Bronx, N.Y., last summer that sickened 133 people, 16 fatally, and an outbreak at a Veteran's Home in Quincy, Ill., that sickened 39 and killed 7.

Michigan officials have been investigating an increase in cases in Flint, Mich., in 2014 and 2015, which resulted in 88 illnesses and 10 deaths, according to a Mar 18 press release from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). The outbreak raised suspicions about a possible link to contamination from a controversial change in the city's water source, but only 31 of the patients lived in homes that received Flint water.

At today's media briefing, Cynthia Whitney, MD, MPH, chief of the respiratory diseases branch at the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said more than half of the cases in Michigan's Genesee County are linked to a single hospital, underscoring the vulnerability of healthcare facilities to Legionnaires' disease outbreaks, especially given that many patients have weakened immune systems.

Drinking water, cooling towers common sources

In the CDC report today, the most common outbreaks locations were buildings that had large water systems, such as hotels, long-term care facilities, and hospitals. The outbreak sources for the 27 Legionnaires' disease outbreaks in today's report were potable water (56%), cooling towers (22%), and hot tubs (7%).

Also on the list was industrial equipment and decorative water features. For two outbreaks, the source was never identified.

Common problems found for 23 outbreak investigations include:

- Process failures (65%), such as not having Legionella water management programs

- Human error (52%), such as not cleaning or replacing a hot tub filter as recommended by the manufacturer

- Equipment malfunction (35%), such as disinfection systems not working

- External water quality changes (35%), such as from nearby construction

Stepping up water management

Frieden said the CDC is calling for improvements in water management programs, and to assist the efforts, it urged building managers and owners to learn about new standards published by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE).

The CDC also launched a toolkit to walk building managers through the process of developing a water management program to reduce Legionella growth, such as developing a team to tackle the issue, identifying areas in the system where Legionella can grow, and deciding where to apply controls and how to measure them.

"The bottom line is that almost all of these infections are preventable," he said.

Frieden also said health providers play a critical role in screening and testing people with serious pneumonia.

The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) today applauded the CDC's report and guidance for water management programs. Louise Dembry, MD, MS, MBA, the group's president, said in a statement, "Guidance on effectively managing this environmental hazard helps all types of healthcare facilities provide safer care."

She said SHEA members have worked on managing environmental sources of Legionnaires' disease before, during, and after outbreak situations, but the CDC's report today fleshes out the scope of the issue.

"The CDC's leadership in reporting the scope of their work on this pathogen, as well as best practices for controlling it, is timely for improving water quality and limiting this public health threat."

See also:

Jun 7 CDC press release

Jun 7 CDC Vital Signs report and MMWR Vital Signs report

Mar 18 MDHHS press release

Jun 7 CDC water management program toolkit

ASHRAE standard 188 on legionellosis risk management

Jun 7 SHEA press release