Legionnaire's disease (LD) cases rose ninefold between 2000 and 2018, and the reasons for the dramatic global rise have been a scientific mystery. This week, a research team proposed a surprising factor: a drop in air pollution.

The study shedding new light on LD cases comes amid new data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showing that Legionella-related outbreaks were the leading cause of drinking water–related outbreaks from 2015 to 2020.

Untangling a mystery

The study probing the reasons for the rise in LD was conducted by a research team from New York who examined several factors that have been suggested in the scientific literature, with an eye toward looking for other explanations. Their findings appear this week in PNAS Nexus.

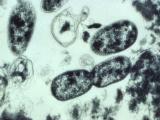

Legionella bacteria naturally occur in freshwater but can grow and spread in water systems such as cooling towers, hot tubs, and hot water tanks. Infections can occur when people inhale aerosolized bacteria or when contaminated water is aspirated into the lungs. Legionella pneumophilia infections are known to disproportionately affect vulnerable subgroups, including minority groups and people with underlying health conditions.

In the past, scientists have weighed many factors behind the steady rise in cases, from the aging population to environmental factors.

For the study, they examined epidemiologic patterns in New York, one of the states with the highest LD burden, and focused on cooling towers, which have been identified as the source in several outbreaks.

Falling sulfur dioxide levels may play a role

When they weighed other factors such as precipitation, temperature, and ultraviolet light, they found that air concentration of sulfur dioxide—a component of air pollution—decreased in New York and the country as a whole over the same period when LD cases rose.

They identified a possible relationship between the two factors based on observational data and calculations. Normally, airborne water droplets containing Legionella take in sulfuric acid from ambient air, making water droplets acidic and inhospitable for the bacteria.

As sulfur dioxide acid levels dropped over the years with declining air pollution, Legionella bacteria survived longer in airborne droplets, raising the risk of infection.

Researchers said reducing sulfur dioxide pollution has many health benefits and shouldn't be discouraged, but they said the possible connection may be helpful for understanding transmission, predicting risks, and designing interventions.

Legionella main culprit in outbreaks linked to drinking water

In a related development, researchers from the CDC this week revealed their findings from tracking waterborne disease outbreaks involving drinking water from 2015 to 2020. They published their findings in a surveillance summary in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Their data came from the National Outbreak Reporting System and for the first time categorized outbreaks as biofilm pathogen or enteric illness related.

Public health departments, regulators, and drinking water partners can use these findings to identify emerging waterborne disease threats.

Legionella outbreaks, which made up most of the biofilm-related category, increased over time and were the leading cause of drinking water–related outbreaks, along with hospitalizations and deaths. The bacteria were implicated in 92% of outbreaks that involved public water systems.

Of the enteric disease outbreaks, about half were linked to wells. The most common pathogens were norovirus, Shigella, and Campylobacter.

Researchers emphasized that most drinking-water illness outbreaks involved multiple factors, such as plumbing issues with LD outbreaks.

"Public health departments, regulators, and drinking water partners can use these findings to identify emerging waterborne disease threats, guide outbreak response and prevention programs, and support drinking water regulatory efforts," the group wrote.