A study today on antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) at small hospitals has found that only the most intensive intervention had an impact on antibiotic use.

The study, in Clinical Infectious Diseases, evaluated different levels of ASP interventions at 15 small hospitals within the Intermountain Healthcare system, which encompasses 22 hospitals in Utah and Idaho. The hospitals were randomized to one of three different ASPs with escalating levels of intensity, and antibiotic use during the intervention period was compared with a baseline period.

Only the hospitals in Program 3, which had access to infectious disease (ID) physicians and actively involved local pharmacists, saw reductions in antibiotic use.

The authors of the study, most of them from the Intermountain system, say the results suggest that implementing ASPs in small hospitals is feasible and can have an impact. But they added that small hospitals within larger healthcare networks are more likely to get the resources and expertise necessary for a robust program. Whether small independent hospitals can achieve similar results remains a question.

Reductions in antibiotic use

For the cluster-randomized trial, all the hospitals—which ranged in size from 14 to 146 beds—were provided an educational curriculum and tools for implementation of basic antibiotic stewardship interventions. Clinicians at all hospitals had access to an ID telephone hotline that was staffed 24/7, and pharmacy directors and hospital leaders were provided monthly, hospital-specific updates on antibiotic use. The hospitals in Program 1 received only these interventions.

In Program 2 hospitals, clinicians received more intense stewardship education and audit and feedback from pharmacists on the use of select antibiotics. Clinicians in Program 3 hospitals received these interventions plus audit and feedback on most antibiotics.

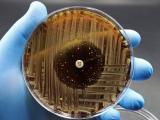

Program 2 and 3 hospitals also implemented antibiotic restrictions on daptomycin, linezolid, imipenem, meropenem, ceftaroline, tigecycline, and all mold-active antifungals. In Program 2 hospitals, local pharmacy staff pre-authorized restricted antibiotics based on defined criteria; in Program 3 hospitals, an ID clinician approved restricted antibiotics and reviewed microbiology results.

The primary analysis evaluated the change in total antibiotic use in each program between the baseline period (January through December 2013) and the intervention period (April 2014 through June 2015), and compared the effectiveness of the programs with each other. The secondary analysis evaluated change in broad-spectrum antibiotic use, restricted antibiotic use, 30-day readmission, 30-day mortality, hospital length of stay, and Clostridium difficile incidence.

The results showed that total antibiotic use declined 11% from the baseline period in the hospitals that implemented Program 3, and use of broad-spectrum antibiotics was reduced by 24% in those hospitals. Hospitals in Program 2 and 1, in contrast, saw no reductions in total or broad-spectrum antibiotic use. Use of restricted antibiotics declined in all hospitals, with hospitals in Program 3 seeing the greatest reductions (86%), followed by hospitals in Program 2 (52%) and Program 1 (41%).

When the researchers compared the magnitude of effect between the interventions, Program 3 hospitals had greater observed reductions in total, broad-spectrum, and restricted antibiotics than Program 1 or 2 hospitals, but the differences were not statistically significant. No statistically significant differences in mortality, 30-day readmission, or length of stay were observed, and C difficile incidence overall was low during baseline and interventions periods.

Although the study didn't assess specific components of the different ASPs, the authors suggest that the more extensive audit and feedback from pharmacists in Program 3, along with daily interactions with an ID provider and more frequent use of the ID hotline, may explain why hospitals in that group saw better results from their ASP.

"These frequent interactions with experts likely resulted in the local prescribers being more engaged and having greater trust in the stewardship process," they write.

Many hospitals lack ASP resources

The authors say that the Program 3 hospitals benefitted from having access to Intermountain Healthcare's ID expertise, resources, and technical infrastructure for measuring antibiotic use, and they conclude that the results highlight how healthcare systems can engage small hospitals in antibiotic stewardship by embedding stewardship support into the healthcare delivery system.

But what about small independent hospitals that lack those elements? According to the study, 38% of small hospitals in the United States are not affiliated with a healthcare network. "Our experience suggests that independent small hospitals will need to identify a champion, access expert resources for assistance (i.e., ID physicians), focus on syndromic based stewardship methods targeting common conditions that are typically more prevalent in small hospitals, and adapt measurement to local capabilities for ASPs to be effective," they write.

Regardless of their size or affiliation, all US hospitals are now required to have an ASP by the Joint Commission, the body that accredits nearly 21,000 US healthcare organizations.

Establishing strong ASPs in small hospitals is important, because a significant portion of healthcare in the United States takes place in these facilities. Nearly three quarters of US hospitals have fewer than 200 beds. And studies have shown that antibiotic use rates and patterns in small hospitals are similar to those of larger hospitals. Yet according to a 2015 survey, fewer than half of these small hospitals had ASPs that met all of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's seven core elements of antibiotic stewardship. Part of the reason for this is lack of resources and ID expertise.

See also:

Feb 23 Clin Infect Dis abstract