A study today in Emerging Infectious Diseases shows that states with bigger investments in public health tracked more foodborne disease outbreaks between 2009 and 2018, suggesting that those with lower investments may miss critical outbreaks.

A related study in the same journal, meanwhile, illustrates how responding quickly to food illness outbreaks not only saves lives but significant money.

'Large benefits' of investing in public health

The research was conducted by scientists at the Colorado School of Public Health, who classified states into high, middle, or low reporters of outbreaks based on how many outbreaks per 10 million population were reported. All outbreaks were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) Foodborne Disease Outbreak Reporting Surveillance System.

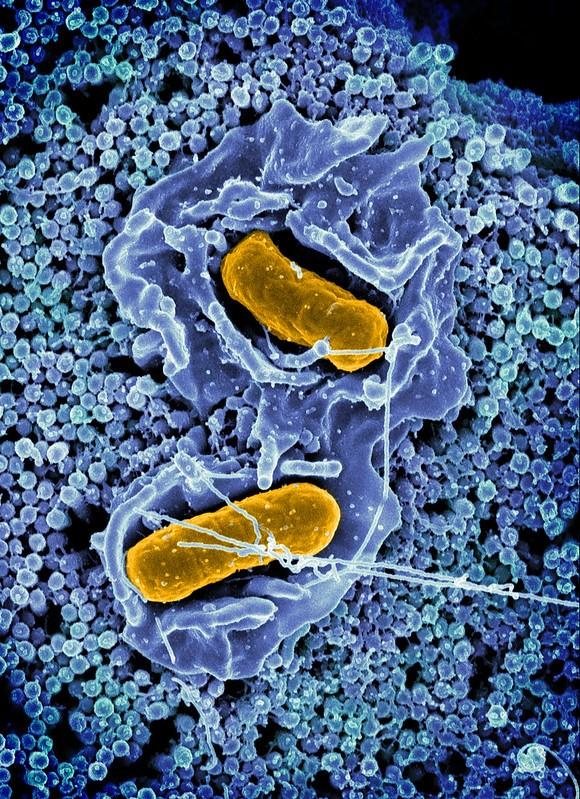

The authors of the study did not include multistate outbreaks in their analysis. Between 2009 and 2018, all 50 states and Washington D.C. reported a total of 8,131 single-state outbreaks involving 131,525 outbreak-associated illnesses. Of these, 74% had a confirmed or suspected etiology, with 47% caused by norovirus, 20% by Salmonella, 10% caused by bacterial toxins, and 3% by Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Overall, states reported a mean of 26 outbreaks per 10 million population per year, with high reporting states averaging 62 outbreaks per 10 million population per year, compared to the 10 states with the fewest number of reported outbreaks (9 outbreaks per 10 million).

High-reporting states reported four times more outbreaks than low reporters, the authors said, but low-reporting states were more likely than high-reporting states to report larger outbreaks.

"Low reporters were significantly less likely than middle and high reporters to report outbreaks with an identified etiology (57% low, 73% middle, 79% high) and reported fewer norovirus outbreaks (4% low, 59% middle, 37% high)," the authors wrote. "Low reporters were also less likely to identify a setting (73% low, 92% middle, 96% high) and less likely to implicate (26% low, 38% middle, 36% high) or confirm (56% low, 75% middle, 75% high) a food vehicle."

High-reporting states had three times the funding for epidemiology and laboratory sources than low-reporting states.

"Investments in public health programming produce large benefits, including increasing the number of foodborne outbreaks reported to national surveillance," said Alice White, MS, first author of the study, in a University of Colorado press release.

Rapid detection, response save money

Quickly identifying—and responding to—a foodborne disease outbreak saves not only lives, but significant money, according to the second study.

Examining the response of a 2018 Salmonella Typhimurium outbreak associated with packaged chicken salad, the authors estimate officials were able to avert 106 cases and $715,458 in medical costs and productivity losses.

Annually, the CDC estimates that 48 million illnesses, 128,000 hospitalizations, and 3,000 deaths are caused by foodborne illnesses in the United States. Of those illnesses, Salmonella accounts for 1.35 million illnesses, 26,600 hospitalizations, and 421 deaths each year.

In 2018, the state hygienic laboratory at the University of Iowa noticed a significant increase in Salmonella in stool samples. The Foodborne Rapid Response team of the Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH) was able to identify the source of the outbreak as prepackaged chicken salad sold by a Midwest grocery store chain. In total, 8 states reported 265 cases of illness, of which 240 were in Iowans. One person in Iowa died, and 94 hospitalizations were recorded.

Using cost of illness estimates for nontyphoidal Salmonella generated by the United States Department of Agriculture/Economic Research Service, the authors estimated the economic costs to society averted by responding rapidly to this outbreak.

"Quantifying and communicating effects such as the amount of illness and economic costs prevented by response and prevention efforts to policymakers and other appropriate audiences using a clear and systematic approach helps to show the value in investing in a robust, responsive, and collaborative public health infrastructure," the authors concluded.