New research by a team of scientists at the University of Wisconsin is shedding new light on what makes the multidrug-resistant and deadly yeast Candida auris so effective at spreading among hospital patients.

In a series of experiments involving lab-created sweat and pig skin, the scientists showed that C auris forms dense, multilayered biofilms on skin that persist even in dry conditions. The scientists say the findings may help explain why the pathogen colonizes the skin, and why it's spreading so easily in hospitals.

"We think that skin colonization involves biofilm growth," said lead study author Jeniel Nett, MD, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. "Because these communities resist drying and persist in the environment, this mode of growth is likely involved in the spread of Candida auris in hospital settings."

The research, published last week in mSphere, comes as hospitals in several states grapple with C auris, which first appeared in the United States in July 2016. According to the most recent case count from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were 950 confirmed and 30 probable hospital cases as of Nov 30, 2019, in 13 states. An additional 1,908 patients have been found to be colonized. Hospitals in more than 30 countries have reported multiple cases.

Originally identified in Japan in 2009, C auris causes severe infections in hospitalized, immunocompromised patients, and has demonstrated resistance to the three most commonly used antifungal medications. While many of the patients who acquire C auris infections tend to be extremely ill, the mortality rates associated with the pathogen range from 30% to 60%. As a result, the CDC has labeled C auris an urgent threat.

Dense biofilms in fake sweat

In addition to high rates of drug resistance, what's making C auris so difficult for hospitals to contend with is its ability to spread easily between patients, which has been linked to the pathogen's affinity for skin.

Unlike other Candida species, which typically colonize the intestinal tract, C auris colonizes the skin of hospital patients. A study last year by CDC researchers also found that colonized patients can shed the yeast onto bed rails and other parts of the hospital environment.

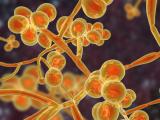

But little is known about the mechanisms driving C auris skin colonization. To explore these mechanisms, Nett and her colleagues created a synthetic sweat medium designed to mimic human axillary (armpit) sweat, then examined the ability of a C auris strain to form biofilms, which are slimy communities of microbes, held together by molecules, that can develop on moist surfaces. These biofilms protect microbes from antibacterials and other environmental stresses when they are outside a host.

Previous research has shown that, compared with Candida albicans, the most prevalent Candida species, C auris doesn't form particularly dense biofilms in traditional growth media. But in the synthetic sweat medium, they observed that C auris formed biofilms that were 10 times as dense as those formed by C albicans.

Research on different C auris isolates obtained from the CDC—from the four distinct clades that have been identified—indicated that the majority demonstrated the same ability to form dense biofilms in the synthetic sweat. Furthermore, when they tested the yeast's ability to form biofilms in concentrated synthetic sweat—an experiment to mimic what happens when sweat evaporates on skin or on skin that has been shed onto a surface—they found that C auris still readily formed biofilms for 14 days.

Subsequent tests performed on pig skin, which was chosen because it shares many characteristics with human skin, including the thickness of skin layers and distribution of skin cells, produced results that were consistent with the in vitro tests: C auris showed enhanced biofilm growth compared with C albicans.

"Because it colonizes skin, we thought that it may replicate in skin niche conditions, including artificial sweat, but were surprised to see this species grow to a much greater burden than it did in traditional media," Nett said. "We think that Candida auris forms similar biofilms on medical devices in healthcare settings and that these communities represent a reservoir of Candida that can be spread among patients, particularly through shared medical equipment."

Writing in a commentary that accompanies the study, Priya Uppuluri, PhD, who studies C albicans biofilms at the University of California, Los Angeles David Geffen School of Medicine, says the experiments reinforce previous reports on C auris hospital outbreaks that have implicated skin colonization as one of the risk factors for infection. The new findings reinforce earlier work "by showing that a biofilm architecture not only serves as a high-burden reservoir of cells that can be shed intermittently upon contact but also provides C. auris with an enhanced ability to withstand the vagaries of environmental stresses," Uppuluri writes.

Nett says that she and her colleagues hope to use the models in this study to develop strategies to prevent or control Candida growth on skin and limit its spread in healthcare settings.

See also:

Jan 22 mSphere study

Jan 22 mSphere commentary

Jan 15 CDC Candida auris case count

Jun 25, 2019, CIDRAP News story, "Study: Colonized Candida auris patients shed fungus via skin"