May 22, 2009 (CIDRAP News) – Officials from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) today unveiled the first comprehensive analysis of the novel H1N1 influenza virus, shedding some light on its source, which appears to be pigs in an area where surveillance gaps exist.

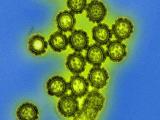

The study of the antigenic and genetic characteristics of the new flu virus appeared today in an early online edition of Science. Nearly 60 researchers from across the globe assisted with the study. They analyzed full and partial genomes of 76 novel H1N1 samples, 17 from Mexico and 59 from 12 US states.

Nancy Cox, MD, director of the CDC's influenza division, told reporters at a CDC media briefing today, "With any new pathogen, it's important to understand the origin to stop reemergence."

Tracing the new flu's ancestors

Each of the eight genetic components of the new virus most closely resembles influenza viruses found in pigs, which suggests novel H1N1 likely originated in pigs, she said, adding that researchers can't tell if humans contracted the virus directly from swine or if an intermediary host played a role.

"The study reinforces that swine are an important reservoir," she said. "The result shows the global need for more systematic surveillance in pigs."

Based on the current data, researchers don't have a hypothesis on what an intermediary host could have been for the new virus. "What we can say is that the closest gene progenitors were circulating in swine," Cox said.

The researchers reported that several scenarios exist for how and where the reassortment event happened that produced the novel H1N1 virus. However, they wrote that divergence from previously sequenced strains, suggested by long branch lengths on the new virus's phylogenetic tree, indicates lack of surveillance for a number of years in the original novel flu host.

The high degree of genetic uniformity among the viral samples analyzed so far suggests that cross-species introduction to humans was a single event or multiple events involving very similar viruses, the group reported.

Researchers still haven't identified what factors are giving the new virus the ability to replicate and transmit in humans but have yet to find the adaptation or transmissibility markers seen in other viruses such as the 1918 H1N1 virus or H5N1.

Antigenic profile

During the analysis of the novel H1N1 samples, the research group also characterized the antigenic properties. Cox said they found that the viruses were very homogenous, showing much less variability, or drift, than seasonal influenza viruses. "That makes our job in coming up with a reference vaccine virus much easier," she said.

Cox said that influenza viruses in swine have been shown to mutate at a slower rate, perhaps because the animals don't live very long and don't have many subsequent infections. However, she warned that now that the virus is circulating in humans, the virus might start mutating similarly to seasonal influenza viruses.

A call for more swine surveillance

Anne Schuchat, MD, interim deputy director of CDC's science and public health program, said the findings of the study underscore the need for animal and human health experts to communicate more closely and conduct joint investigations.

Cox said animal health officials in the United States conduct some swine surveillance, but in other parts of the world the activity is much more limited. "That's where we see the greatest gaps," she said.

Marie Gramer, DVM, PhD, a swine flu expert at the University of Minnesota, told CIDRAP News that formal surveillance for swine influenza isn't conducted due to a lack of coordinated funding and effort.

Gramer pointed to some tensions between human and animal health communities that some veterinary experts believe have been fanned by steady messaging from the CDC and World Health Organization that pigs and poultry are the source of all pandemics, an impression she says has hurt the animal agriculture industry.

She said it isn't realistic to expect the animal agriculture industry, reeling from the financial effects of influenza suspicions, to fund and research surveillance for all of its animal health issues.

"Influenza viruses are shared between people and animals," Gramer said. "Surveillance should be done jointly, not separately."

Garten RJ, Davis CT, Russell CA, et al. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A (H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science 2009 May 22; early online publication [Abstract]